Resources and Articles

Getting the most out of OALD

Read Vol.3

In my final article in this series, I will share how to use the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary to its fullest potential. First, I will introduce some methods for using OALD with intermediate students and learners who are planning to use it in the future. Then, I will explore further ways for advanced users (including teachers) to fully utilize the app’s Full text search function. (For more information about the app, read my previous article.)

Part One: Tips for Using OALD with Intermediate Students and Future Users

OALD is an English-English dictionary for advanced learners. For intermediate learners, other resources such as Oxford Wordpower Dictionary are available. But that doesn't mean intermediate-level learners can't use OALD. Here is a list of ways to help intermediate students get familiar with OALD, and use it to improve their English skills.

1. Try reading the easy parts!

- Example sentences and columns

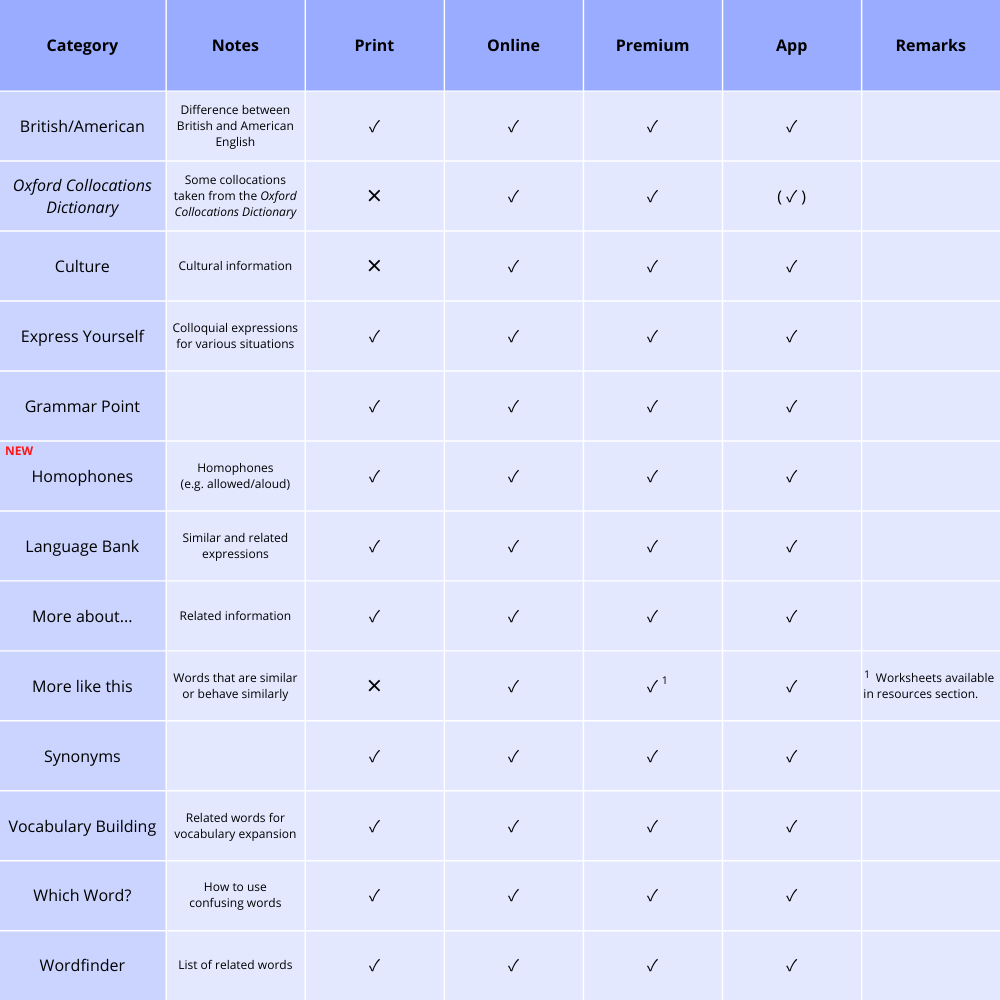

English-English dictionaries are challenging. Definitions can be dense, abstract, and confusing1. That said, some parts are relatively approachable. In OALD, examples and columns are written in ordinary English, so they are easy to understand. Key English language learning points, such as usage, synonyms, and cultural information, are covered in the various columns (see the table "Columns" at the end of my second article). Learners should read the sections that interest them.

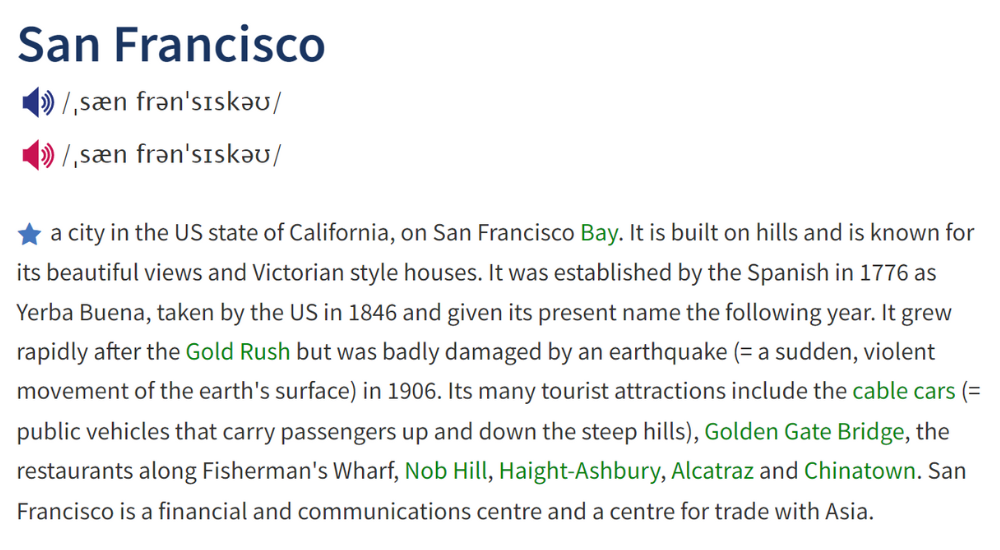

- Encyclopedic information

While early English-English learner’s dictionaries focused on language-related information, more recent publications include encyclopedic information. OALD also contains quite a few entries about people's names, place names, and historical events. These are explained concisely, in plain English, and with relevant information, making learning fun and educational:

2. Review familiar vocabulary!

- Basic language

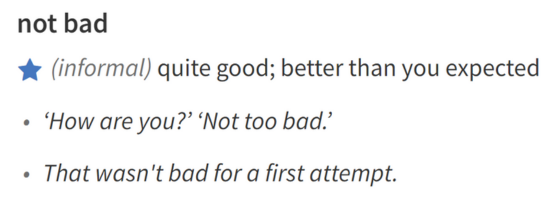

As is often pointed out, it's good to look up words you have already learned in an English-English dictionary. Since you already know the meaning in your first language, it is easier to understand the definition, and it can be an eye-opening experience for learners. In my Guide to the practical usage of English monolingual learners’ dictionaries (p. 9), I suggested looking up the words not bad, climb, international, and willing in order to draw the reader’s attention to the gap between the Japanese translation and the English meaning. Not bad literally translates to warukunai in Japanese, but the English definition reveals that the phrase in fact has a more positive connotation:

- Loan words found in English

Definitions of words that have entered English from your language should be familiar and easy to read. As far as Japanese is concerned, by entering Japanese as the keyword in the Advanced Search on the CD-ROM accompanying OALD 8, you will find the following Japanese-origin and Japan-related phrases:

aikido, anime, Bon, bonsai, bonze, bullet train, bushido, butoh, futon, geisha, hiragana, ikebana, ju-jitsu, kabuki, kanji, karate, katakana, kendo, kimono, manga, miso, ninja, Noh, obi, origami, pachinko, romaji, sake, sashimi, shiitake, Shinto, Shogun, soy sauce, sumo, sushi, tatami, tea ceremony, tempura, teriyaki, wasabi, yukata, Zen

As of March 2023, the following phrases have been added to the online OALD2:

bento, cosplay (noun, verb), cosplayer, edamame, emoji, hibachi, kanban, matcha, mecha, ramen, TabataTM, Wagyu, yuzu

3. Check the items in bold!

- Usage patterns

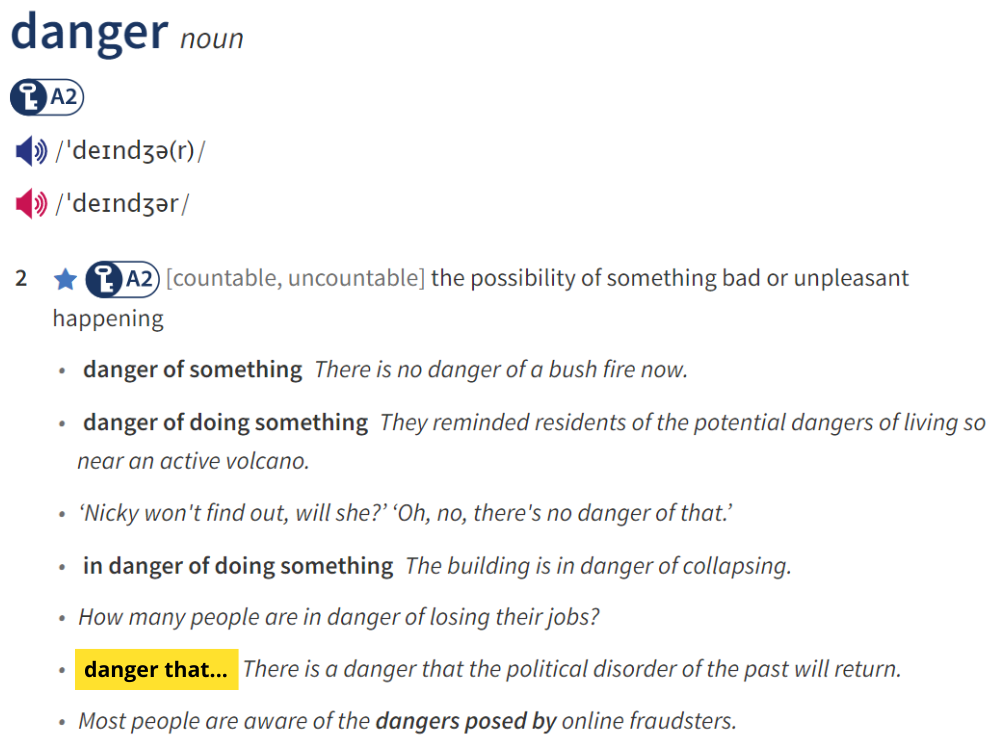

In addition to headwords, OALD also employs boldface. Usage patterns, and prepositions and adverbs used with the headword are highlighted in bold. This makes it possible to check aspects of usage which even advanced students need to pay special attention to, such as whether or not a noun can be followed by an appositive that-clause:

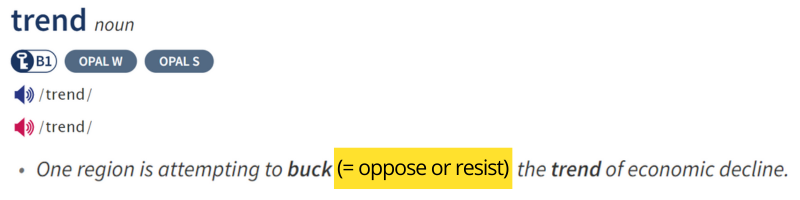

- Set phrases

Set phrases and important collocations used in example sentences are also shown in bold. Where the meaning is not clear, a note in brackets is provided:

It is important to learn these words and phrases in bold, as they are useful for both productive and receptive language skills.

4. Look up anything using Full text search!

I will cover the app's Full text search function more comprehensively in the next part, but it’s worthwhile mentioning here that intermediate users can also use it to search for whatever word or phrase that interests them. For example, if you search for World Cup, you'll find fascinating examples scattered throughout OALD that are both memorable and handy for conversation:

- They crashed out of the World Cup after a 2–1 defeat to Brazil. (s.v. crash out)

- The team are ready for next week's World Cup clash with Italy. (cup 4, Extra Examples)

- The victory keeps San Marino's dream of a World Cup place alive. (dream 2, Extra Examples)

- They were disappointed by the team's early exit from the World Cup. (s.v. exit 4)

- World Cup fever has gripped the country. (fever 4)

- He's been chosen to represent Scotland in next year's World Cup Finals. (s.v. represent 3)

Part Two: Full text search for Advanced Learners

In my previous article, I introduced the Full text search function available on the OALD app as follows:

Full text search allows you to search for headwords, idioms, and example sentences based on single or multiple key words. Notes attached to example sentences, extra examples, and other columns are also searchable. This function also picks up words and phrases which are not headwords, idioms, and other subheadings, making searching on the app more comprehensive, more flexible, and complementary than the online version, which doesn’t allow such searches.

A large proportion of advanced users must be language teachers. Many teachers, myself included, use OALD not only for their own searches, but also for class preparation. I am very indebted to Full text search. Although it is not limited to teachers, we will look at additional ways to use Full text search in the second half of this article.

1. Comprehensive search: Check whether the word is included or not

I have been teaching English at university for more than a quarter of a century. I have used English-English dictionaries to prepare for classes, and have created and distributed materials based on the English-English dictionary for about a third of those classes. I haven’t always prepared perfectly. In fact, twice I've had a student point out that I overlooked a phrase, and that the phrase is listed there in the dictionary. Had Full text search been available, I could have double checked and avoided that embarrassing mistake.

Full text search can be used to find out whether a word or phrase is included in OALD as a headword, idiom, or example sentence. For example, you can instantly see that in plain view, which is not entered as a phrase, is included in Extra Examples under sense 2 of view (The knife was in plain view on the kitchen table.). The saying Fine feathers make fine birds is not listed at all. The phrase like it or not is not listed as such, but Full text search shows us that it is included in an example sentence under sense 2 of whether (I'm going whether you like it or not).

2. Pinpoint searches for definitions

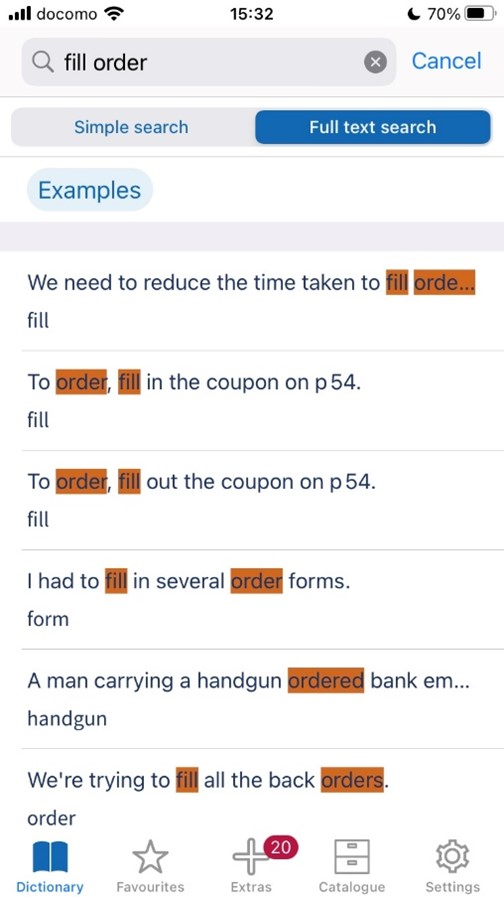

Some words have different meanings depending on use and context. For example, what is the meaning of fill in the sentence below?

It [The milk froth] should be nice and airy, yet firm at the same time, which is not an easy order to fill.

(Morita, Akira. 2014. Teacher's Manual for BBC World Profile on DVD. Nanundo. 94.)

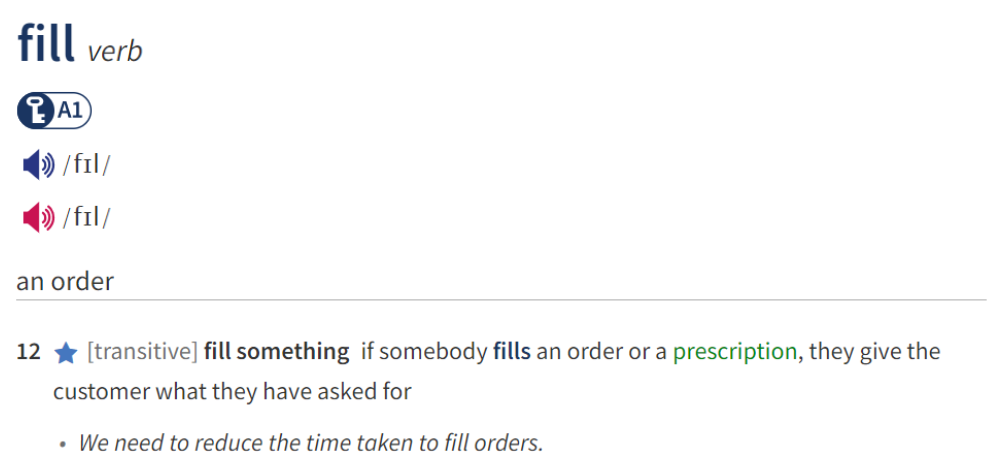

Even with Shortcuts (subheadings which show the general meanings of a headword), searching polysemous words can be onerous even for advanced users. With that in mind, a Full text search using the keywords fill and order yields the following hits:

If you tap on the first example, which appears to be the most relevant, you can see that it corresponds to sense 12 of fill:

3. Improve your vocabulary with Full text search

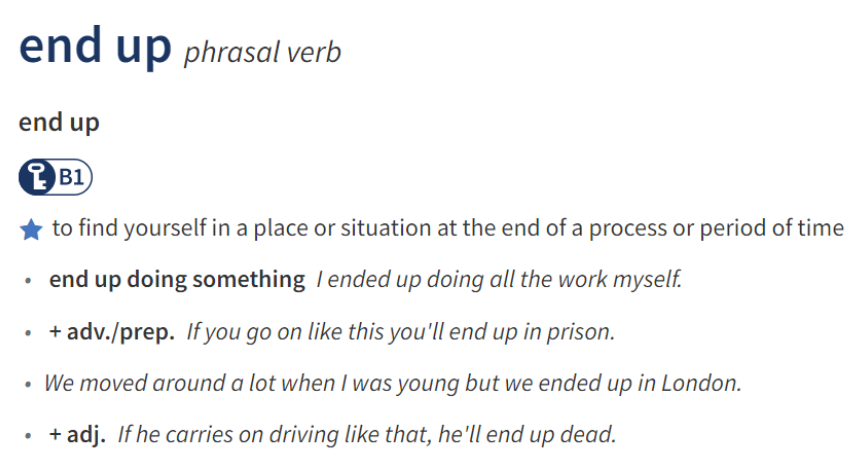

Advanced users can also use Full text search to improve their English knowledge. Learners can search for the words and phrases they are interested in, and examine the example sentences to see how they are used, paying attention to meaning, nuance, collocation, and context. For example, if you look up end up, you will find that the phrasal verb has the following usage patterns:

By conducting a Full text search for example sentences rather than just for headwords, you will find a greater variety of results from all dictionary texts:

・In end up doing something, not is placed before the ing form of the verb:

- For all their talk of equality, the boys ended up not doing any cooking. (s.v. talk noun 4, Extra Examples)

・End up can be followed by these adverbial and prepositional phrases:

- We got lost and ended up miles away from our intended destination. (destination, Extra Examples; intended 1)

- I usually end up with gravy down my shirt front. (front 1, Extra Examples; shirt front)

・When end up is followed by a noun, as is often added:

- Without education, these children will end up as factory fodder (= only able to work in a factory). (fodder 2)

- ‘Maybe you'll end up as a lawyer, like me.’ ‘God forbid!’ (God/Heaven forbid (that…))

- I started as a trainee and ended up a supervisor. (start verb 6, Extra Examples)

・End up can be used with the following set phrases:

- The scene with the elephant ended up on the cutting room floor (= was not included in the final version of the film). (s.v. cutting room)

- The firm ended up deep in debt. (deep 14)

- His attempts to arrange a party ended up as a comedy of errors (= he made so many mistakes it was funny). (s.v. error)

- The economy went into recession and taxpayers ended up footing the bill. Sound familiar (= does that sound familiar)? (s.v. sound verb 1)

OALD’s example sentences are not a corpus. However, they are a carefully screened collection of high-quality examples which illustrate the meaning of headwords. By scrolling or tapping, you can immediately check the definition of the word in the example sentence. You can also check the importance of words based on CEFR (Common European Frame of Reference) and OPAL (Oxford Phrasal Academic LexiconTM), amongst others. (For more information read my first article.) Idioms in example sentences are shown in bold and are often accompanied by notes. The ability to quickly look up meaning, grammar, and pronunciation all in one place is utterly invaluable.

In this series of four articles, I have written about the past and present of OALD, the differences between paper and digital versions, the functions of different media, the impact of digitization on information presentation and search, and hints for effective use. These are just some of the things I've been thinking about while researching English-English dictionaries for foreign learners and actually using OALD in my own learning and teaching. I hope that my blogs will help you become familiar with this wonderful resource, and that through the ideas I have introduced you will be able to use it even more effectively.

Notes:

1 With the introduction of defining vocabularies of about 3000 basic words (the Oxford 3000TM in the case of OALD) and full-sentence definitions, definitions in contemporary learner’s dictionaries have become much easier to understand (please see my first article). There is a useful video within the premium online resources called “Understanding dictionary definitions” which explains that the words below are frequently used in definitions and are useful not only for understanding definitions but also for describing things when you don’t know the exact word in English:

process, substance, instrument, act, organization, state, quality

2 In August 2022 many words of Korean origin, such as bibimbap, were added to OALD.

(https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/wordlist/new_words)。

3 As the topic is Latte Macchiato, order here has a double meaning: ‘requirement’ and ‘request’.

Reference:

Yamada, Shigeru. 2014. Guide to the practical usage of English monolingual learners’ dictionaries: Effective ways of teaching dictionary use in the English class. Oxford University Press.

https://www.oupjapan.co.jp/sites/default/files/contents/catalogue/oald/media/oup_guide_to_dictionary_use_2014_e.pdf

- About the author -

Shigeru Yamada

Professor at Waseda University, Tokyo. He is on the editorial advisory board of Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America. He was a Co-Editor-in-Chief of Lexicography: Journal of ASIALEX. His specialization is EFL and bilingual lexicography. His publications include “Monolingual Learners’ Dictionaries – Past and Future” (The Bloomsbury Handbook of Lexicography, 2nd ed., Ch. 11, 2022)

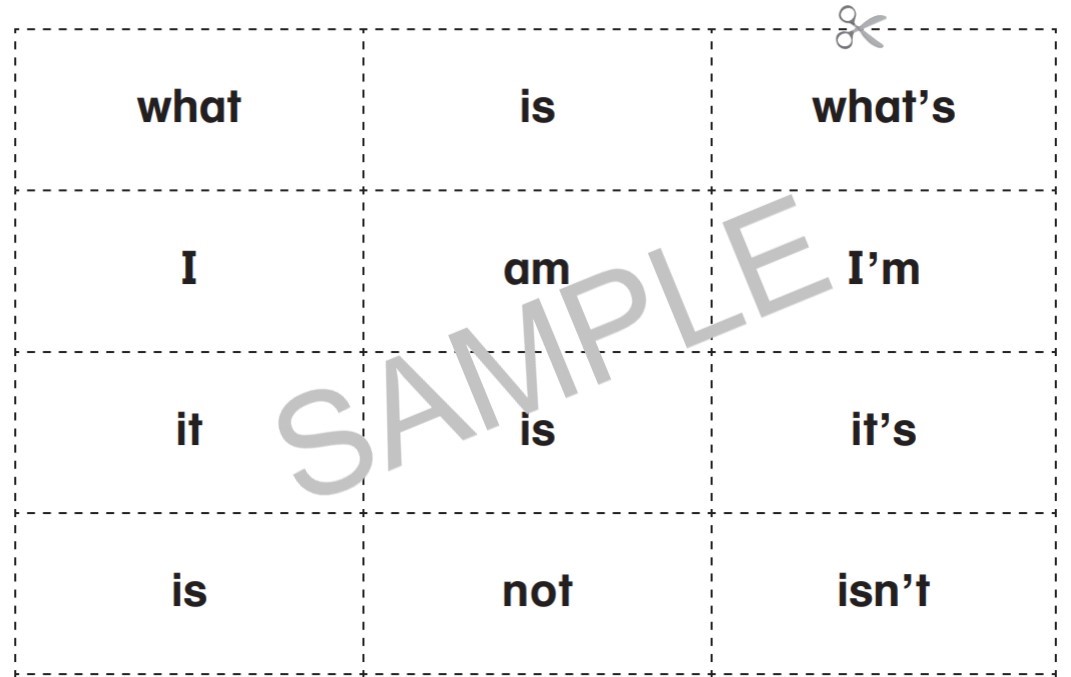

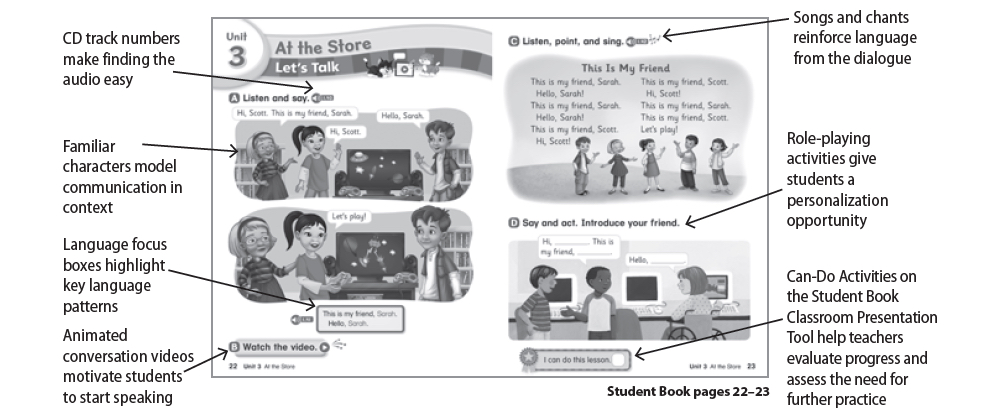

Flipped Learning With Let’s Go and the Gamerize Dictionary

What could you do if you came to class and your learners were already able to accurately spell and pronounce the target language of the lesson? I recently asked Let’s Go author Barbara Hoskins Sakamoto. Her response?

“The sky is the limit!”

She then proceeded to provide concrete examples of all the exciting things teachers could do to help learners use language in meaningful and authentic ways in order to “own the language” in Barabara’s words.

In this article, we will look at flipped learning and how it can help us use the Let’s Go Series as a springboard to motivating language activities that allow learners to use English for genuine communication.

What is flipped learning?

Flipped learning has in a sense been used in educational practice in Japan for many years under the name “yoshu” which translates as preview. Flipped learning is the process of having learners 'pre-study’ content for a lesson with the aim of minimizing the amount of direct instruction done in class and maximizing opportunities for active learning.

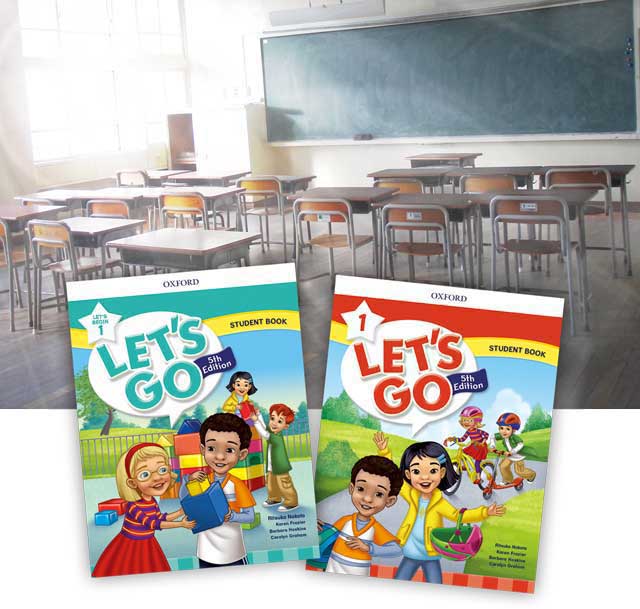

The Gamerize Dictionary

The Gamerize Dictionary is a gamified language learning app that allows students to practice with spelling, grammar and speaking following any curriculum content, including the Let’s Go series. Through a variety of games in the Gamerize Dictionary learners are given ample opportunities to practice listening, reading, writing and speaking directly related to their course content. Though traditional worksheets or workbook activities can be used for flipped learning, the Gamerize Dictionary has the following advantages:

| Worksheets | Gamerize Dictionary | |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback |

Learners receive delayed feedback on errors. This can be less effective for improving accuracy. |

Learners receive immediate feedback on accuracy. This helps improve accuracy and confidence.  |

| Repetition & Recycling |

- 8 to 15 practice examples per page. |

- Up to 64 practice examples per 10 - 15 minute session  |

| Learner Needs |

- One worksheet assigned regardless of level. |

- Content for learners can easily be differentiated for different levels.  |

| Pronunciation |

- No feedback on pronunciation |

- Quick and accurate feedback on pronunciation. |

| Support & Scaffolding |

- Learners can use the accompanying textbook to access answers, but this often leads to copying answers which yields poor results in terms of retention. |

- Learners are able to access audio and written forms of the content before or after activities, helping them recall the information during games. |

| Spelling |

- Learners are able to practice writing answers by hand. |

- Learners are able to use a scaffolded keyboard to spell words but are not able to practice writing by hand.  |

| Motivation |

- Some learners find worksheets to be a chore. |

- Minigames make practice fun.  |

| Review |

- Let’s Go has a spiral syllabus with many opportunities to encounter recycled language. |

- Spaced repetition system ensures learners have enough review at the best timing to ensure retention and automaticity.  |

The Gamerize Dictionary ensures that learners can practice target language independently even before they have learned the content in class. Furthermore, they are able to repeat and review content receiving immediate feedback until they can confidently produce it on their own. This makes it ideal for flipped learning and making the most of limited class time.

The Sky's The Limit

Imagine you come to class and start introducing language for a new unit only to find that your learners are already proficient at producing the language orally and in written form. “Fantastic! Well my job is done here” you might think. Then again, you might also think “What am I going to do for the next 55 minutes?” With all of this extra time, one might be inclined to move on to the next unit or add another course book to your class. However, what this situation presents is an opportunity to take the next step in learning. Getting your learners to think and communicate using what they have studied.

Let’s Go 5th Edition Level 4

Flipped Lessons at Yellow Banana Academy

I joined Naoko Amano, owner of Yellow Banana Academy, veteran teacher and longtime user of Let’s Go to discuss some of the ways she uses Gamerize Dictionary and takes learning to the next level in her classes. Here are some of the ideas she shared with me.

Planning a Trip

In this lesson, the learners enjoy planning a trip of their choice and deciding on what to pack. The stages of the lesson are.

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

|

Setting context and getting interest |

Watch videos about exciting travel destinations. This can be done with or without sound. Don’t treat this as a listening comprehension activity.  |

|

Task 1: Deciding on a destination & Activities |

The learners then:  |

|

Task 2: Deciding on what to bring |

- Using the worksheet once again, the learners talk about what they need to bring on the trip and write down their list. |

|

Task 3: Presenting the plan |

- The learners face another group and present their plans to each other. The worksheet now acts as a prompt, again making the task more achievable. |

|

Task 4: Writing |

- The lesson is rounded off with the learners summarizing their plan in a short piece of writing. |

This lesson plan allows for varied interaction between students, multiple opportunities to use language from the course through different skills, personalization and also opportunities to fill in the gaps with new vocabulary that they need to execute the tasks. In this way, they are starting with familiar language that they have learned through Gamerize Dictionary, and this opens up more opportunities to learn language without feeling overwhelmed.

Ideas from the Author

When it comes to creative ideas for how to take lessons and to turn them into experiences that get students to push their limits and use English for communication, Let’s Go author Barbara Hoskins Sakamoto has no shortage of ideas. For her it is important for learners to have opportunities to say something meaningful to an audience. In other words, the learners should say something that they want to communicate to one or more people. This can be achieved in many ways and the following are some of her ideas for making the content come alive in the classroom.

Puppet Shows: Puppets are a great way to get learners to speak and take risks. Learners can use puppets to act out dialogues found in the Let’s Go and build on those with original input or create their own dialogues and act them out in a puppet show.

Making Books: Students can create their own storybook, gradually adding content at they go through a unit. For example, Barbara recalled one student who loved cats and during a unit on daily routines, the student created a cat as the main character in her storybook. She started by sequencing pictures of the cat's daily routine and making a basic outline and from there gave ideas about what the cat was doing. She then added extra detail extended the language, such as moving from “The cat takes a nap” to “The cat takes a nap on the bed”. Once this was complete the student presented the story.

Making Games: When learners play games with language that they are already confident with, they have more control of the game. They can negotiate the rules together or create new ways to play. This process is natural for children and an example of authentic communication, providing opportunities for them to talk about the game using language learned in the course, or building language beyond it as well.

Making Videos: Once learners have already developed a level of confidence with the target language in a unit, they can try creating videos. For example, after a unit on the weather, they can then create a weather report. To get the most communication out of a task like this, give students autonomy to control video equipment, decide roles, suggest props or gestures, start and stop recording and reviewing their work giving them a natural need to communicate.

Another great aspect of videos is that they can be shared for others to see, including parents, or even a school in another country!

Flip Your Classroom

Teachers and the classroom are valuable resources for learners, but there are things they can do on their own. If students only have a limited amount of time in class each week, why not let them use that time for the things they can only do in a classroom, not things they can do on their own? By cutting down on time spent on drilling grammar vocabulary and spelling we can make sure that our learners are making the best of their time in class and getting the genuine experience with using English.

Learn more about the Gamerize Dictionary here.

OALD: The Impact of Digitalization on Information Search

In this article, I would like to explore the impact of digitalization on how we use dictionaries to search for information. To highlight the strengths of the OALD’s digital search functions, I will focus on the following two points: Headword identification, the fourth of Hartmann’s 7 stages of dictionary searches1 (4 External search [macrostructure]) which has the most conspicuous influence from digitalization, and Full text search, an application which significantly increases the search range and flexibility.

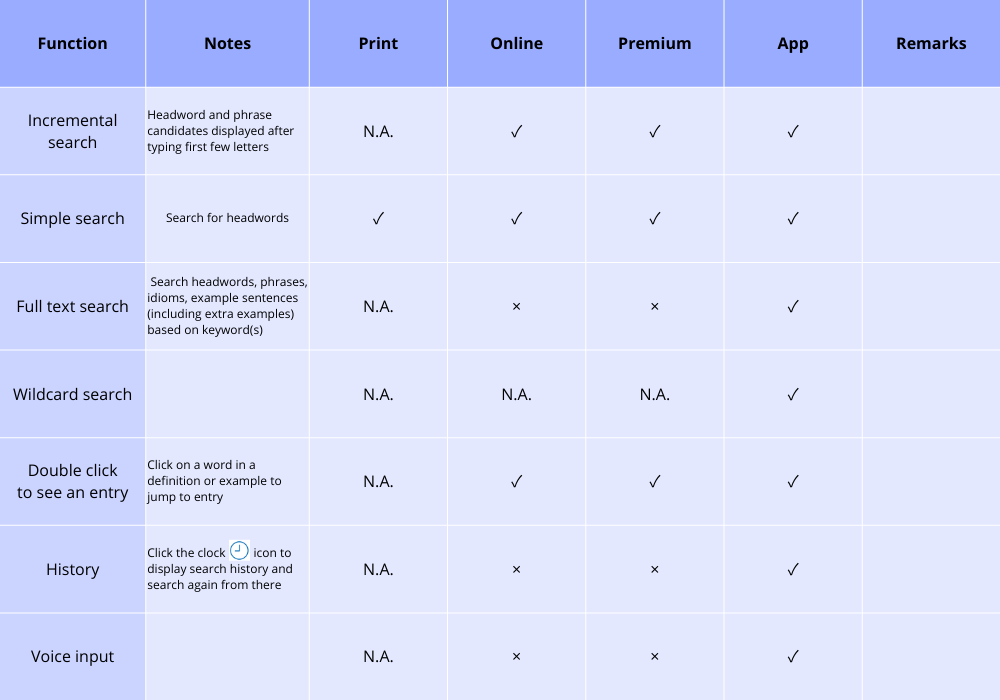

Headword Identification

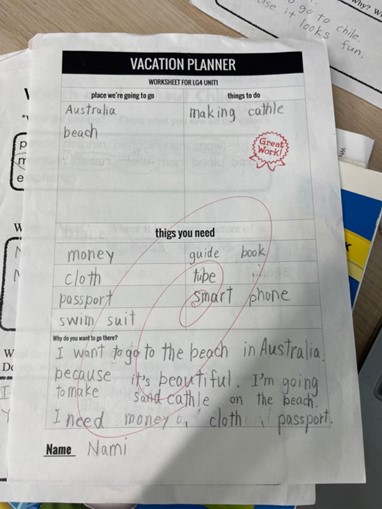

Thanks to digital technology, it is much easier to find the right headword. Functions such as incremental search, wildcard search, and voice input (the latter two only available on the app) allow us to search for words even without knowing the exact spelling. You can also see your search history when using the app2. Searching for idioms is also easy. For example, when searching for kick the bucket, you don’t need to worry about whether to search for kick or bucket. You can simply enter the entire idiom. Digital formats also make searching easier by displaying several candidate words and phrases. By the time you have entered kick t, kick the bucket has already appeared in the drop-down list. In the app version, by the time kick the has been entered into the search box, kick the bucket appears in the list of candidate phrases:

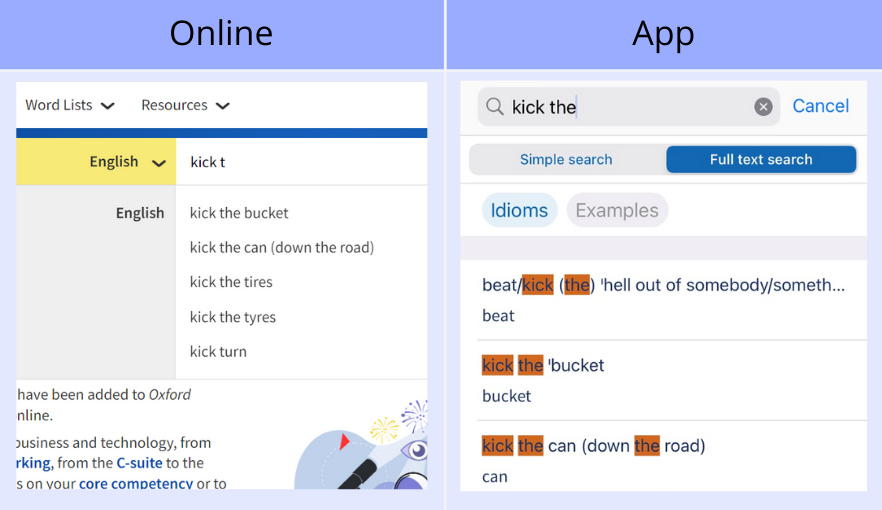

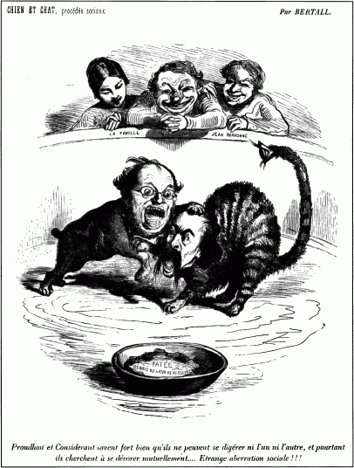

Incremental search has an educational value. For example, when searching for the phrasal verb fight out (which you can see in context in the excerpt below), just by typing fight, fight it out appears as a candidate phrase, teaching you that it is a set phrase.

Quotation:

Considerant and Proudhon fight it out. The caption reads: “Proudhon and Considerant know very well that neither one can digest the other. Nonetheless each seeks to devour the other. … A strange social aberration!!” Cartoon by Bertall, Le journal pour rire, February 24, 1849, reprinted in Bêtisorama. Photo by Harvard University Library Reproduction Services. By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Beecher, Jonathan. “Chapter 11 - June 13, 1849” Victor Considerant and the Rise and Fall of French Romantic Socialism, Part Ⅲ Revolution. (California: University of California Press, California Scholarship Online, 2001), pp.246-266.

(https://academic.oup.com/california-scholarship-online/book/35523/chapter/305721089?searchresult=1#305721219)

Full text search

Full text search allows you to search for headwords, idioms, and example sentences based on single or multiple key words. Notes attached to example sentences, extra examples, and other columns are also searchable3. This function also picks up words and phrases which are not headwords, idioms, and other subheadings, making searching on the app more comprehensive, more flexible, and complementary than the online version, which doesn’t allow such searches.

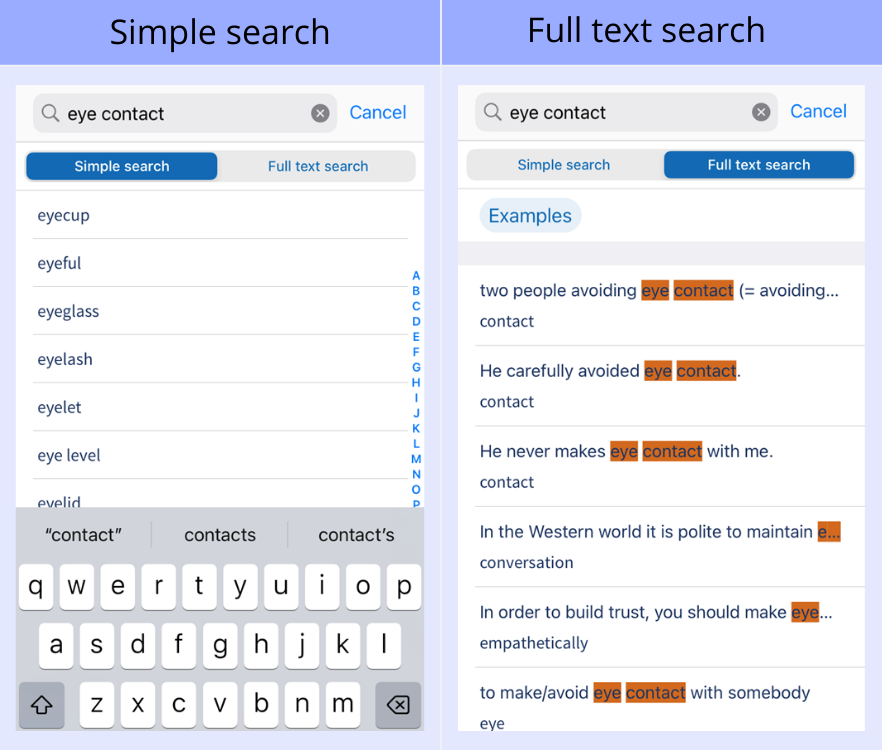

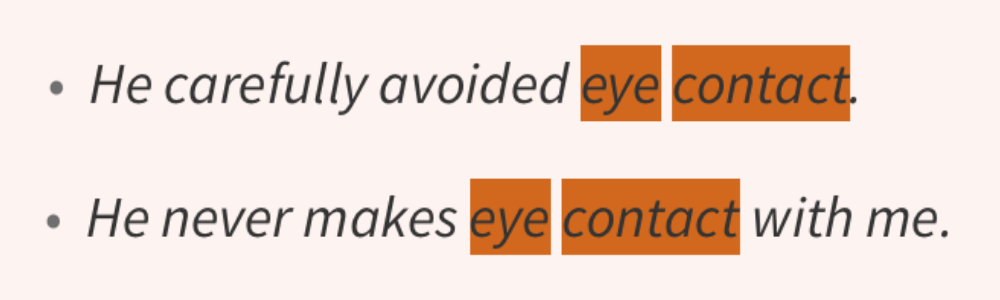

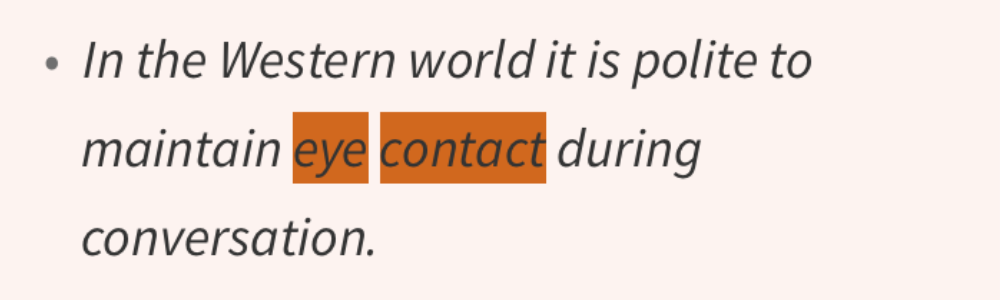

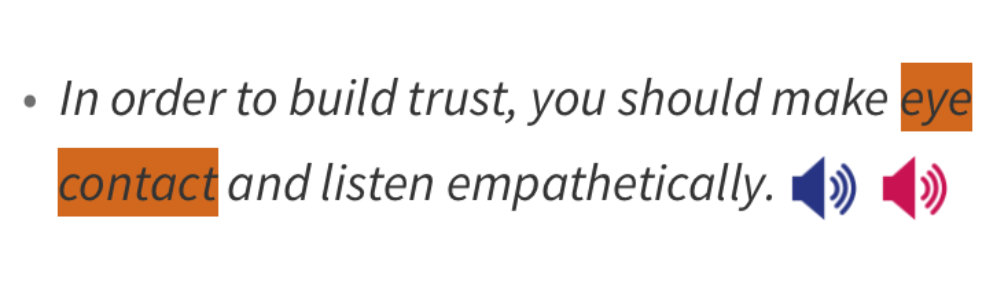

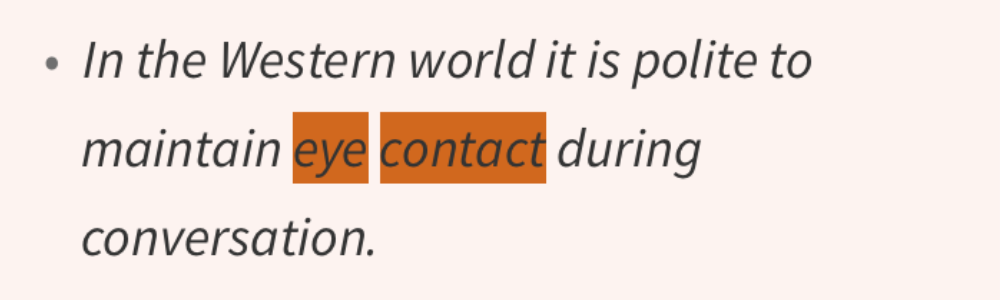

For example, if you search for eye contact using Simple search, it does not appear on the list of candidates, showing you that this is not a headword. If you search using Full text search, 8 example sentences appear:

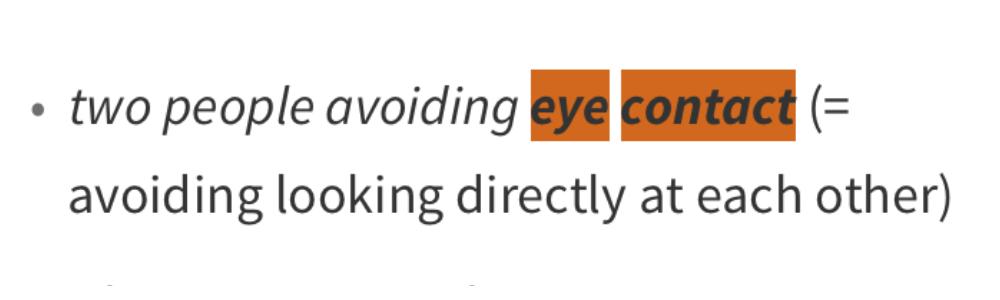

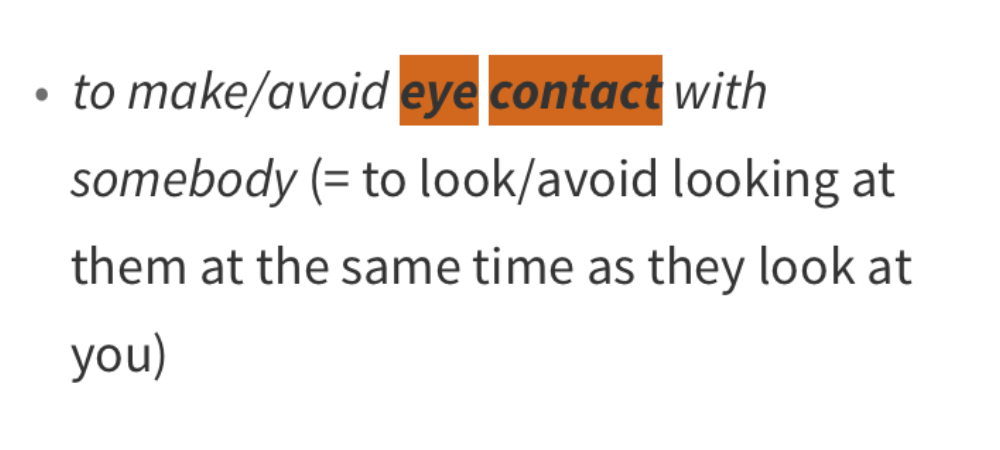

If we look closely, we can see that eye contact are written in bold type in the example sentences under the respective entries for contact and eye:

The conventional process for looking up words (headword → definition → example sentence)4 has been reversed here. This is something wonderful which cannot be done with a paper or online dictionary. As we can see from the 6 examples below, useful collocations, context, and cultural information are also provided:

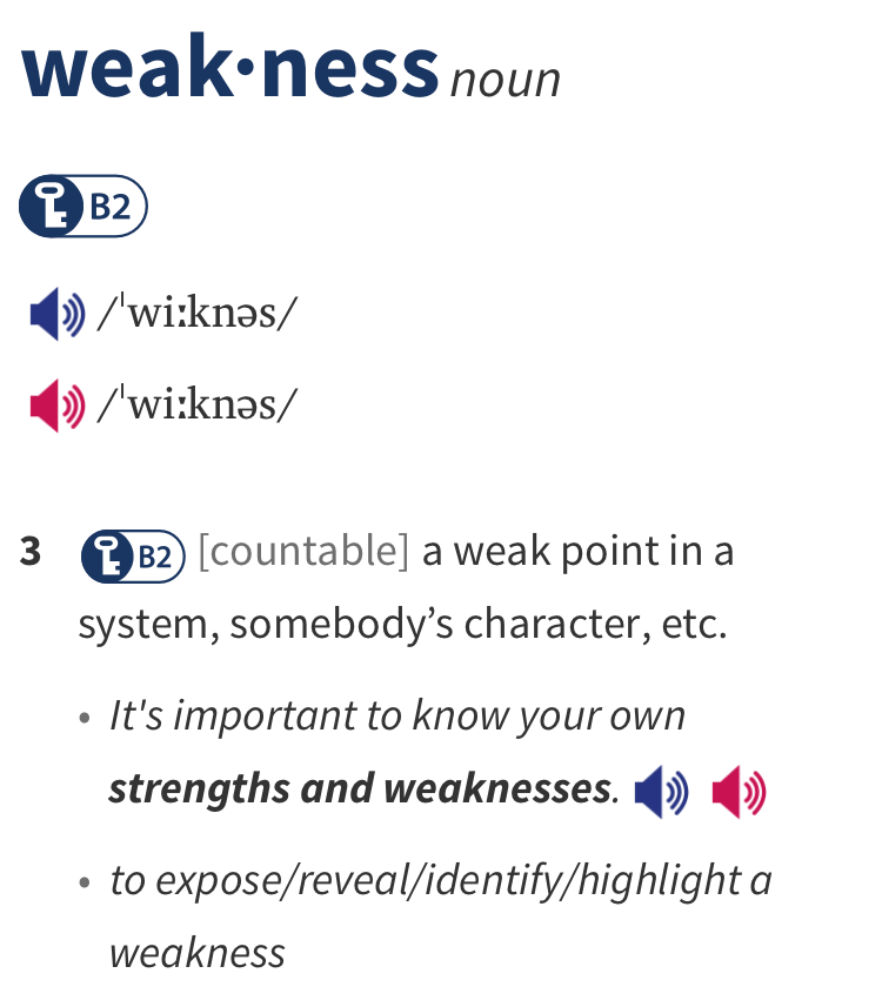

Finally, I would like to look at 2 complementary ways of using Full text search. By “complementary search”, I mean ‘a search performed to supplement the description in the dictionary’. As we can see from the entry for weakness below, OALD traditionally uses forward slashes to save space and present several collocations:

As an inquisitive student, you would like to know in what context each collocation is used. If you conduct Full text search using the keywords expose and weakness, reveal and weakness, etc., the search engine will search through OALD and display examples containing these words.

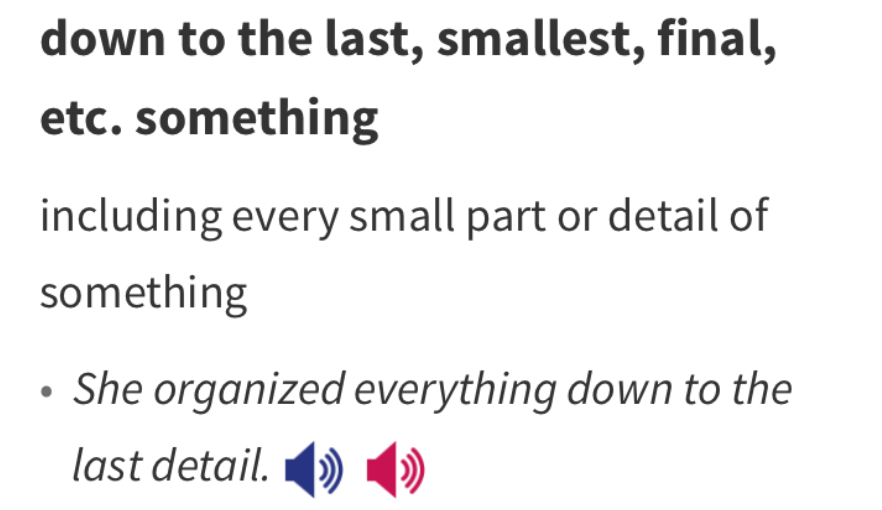

Some phrases have variations. The example below shows the following pattern:

down to + adjective (superlative, etc.) + noun

(In OALD, “etc.” shows that other options are possible6.):

If you want to know what kind of adjectives and nouns this pattern is used with, try Full text search with the key words down to the. There were 7 hits and most of the examples contained … down to the last detail. 6 of the examples contained the verb plan. This showed a useful pattern containing the verb (plan … down to the last detail). There was also an example sentence containing down to the smallest …:

Everything had been planned down to the smallest detail.

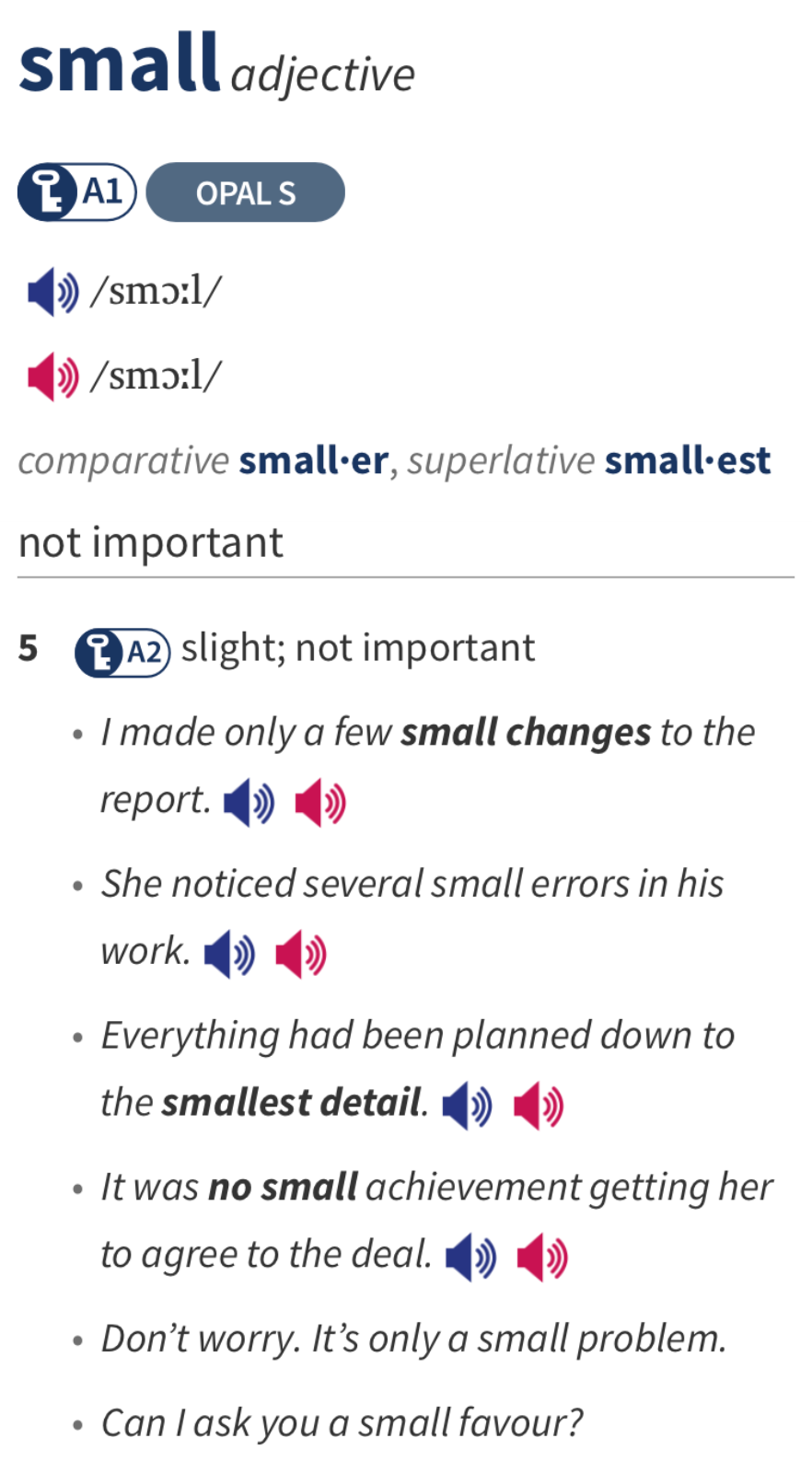

A tap on the example takes you to the original entry, small (adjective, sense 5), teaching you the adjective is used in the sense of ‘slight, not important’:

Using Full text search and bringing examples sentences together in one place, certain things become clear. Tapping an example sentence brings up an entry for the source. You can deepen your understanding by checking definitions and other example sentences as appropriate.

Notes

1 Hartmann (2001: 89-92) abstracted dictionary lookup into seven steps. Although based on using a paper dictionary, it provides a useful model that applies to searches for both receptive and productive purposes. Researching information in a dictionary is complicated, requiring users to follow these steps to get to the correct answer:

- 1) Activity problem

- 2) Determining problem word

- 3) Selecting dictionary

- 4) External search (macrostructure)

- 5) Internal search (microstructure)

- 6) Extracting relevant data

- 7) Integrating information

2For information on which search functions are available in paper, online (free/premium), and app versions, see the table "Search" at the end of my previous article, "OALD: The Impact of Digitization on Information Presentation". Please refer to:

https://www.oupjapan.co.jp/en/kidsclub/articles/teachers/index.shtml#OALD_202211

3Etymology is not covered.

4Since the meaning of a word can be identified by using example sentences similar to the sentences being read, it is also possible to use this process for looking up words: headword → example sentence → meaning.

5There are 54 extra example sentences for conversation, and it's hard to find the ones that include eye contact. Without using Full text search, there is no way to know that example sentences containing eye contact exist.

6 Slots may be indicated by “…” without representative words shown (e.g., in terms of something | in … terms).

Reference:

Hartmann, R. R. K. 2001. Teaching and Researching Lexicography. Pearson Education.

Author Profile

YAMADA Shigeru

Professor at Waseda University, Tokyo. He is on the editorial advisory board of Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America. He was a Co-Editor-in-Chief of Lexicography: Journal of ASIALEX. His specialization is EFL and bilingual lexicography. His publications include: “Monolingual Learners’ Dictionaries – Past and Future” (The Bloomsbury Handbook of Lexicography, 2nd ed., Ch. 11, 2022)

Guide to the practical usage of English monolingual learners’ dictionaries: Effective ways of teaching dictionary use in the English class (2014, Oxford University Press)

https://www.oupjapan.co.jp/sites/default/files/contents/catalogue/oald/media/oup_guide_to_dictionary_use_2014_e.pdf

OALD: The Impact of Digitalization on Information Presentation

Read Vol. 1

Dictionaries were once thought of only as a printed reference work. However, from around 1990, English dictionaries for learners became available on portable electronic devices, CD/DVD-ROMs, and the internet. These days, dictionary apps are easily accessible on smartphones. In this article, I will explore the impact of digitalization on how information is presented in dictionaries.

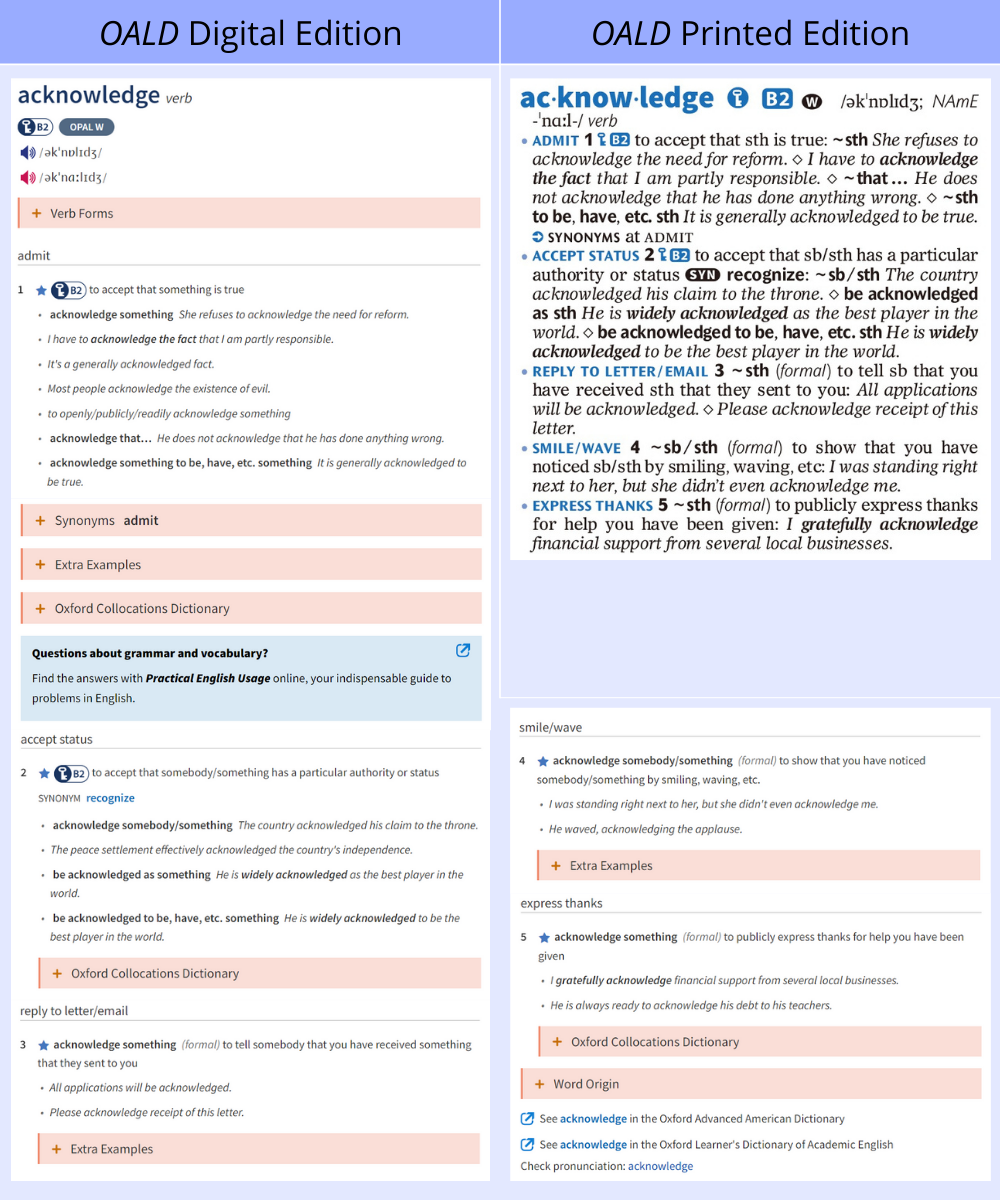

Let's compare the entries for the word acknowledge in the paper and online versions of the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary 10th Edition (OALD10). Whereas the online version has a very clear layout, the print publication employs numerous symbols and abbreviations to maximize the limited space and enrich the content. Digitalization has granted designers greater space in which to present information in an easy-to-read format. Unlike the printed edition, the online version has line breaks for phonetic symbols, shortcuts, definitions, and individual examples. This creates more white space making it easier on the eyes.

Furthermore, you will notice from the example below that some information is found only in the online dictionary. Here, users can click the plus sign to expand the text.

+ Verb Forms

+ Synonyms admit

+ Extra Examples

+ Oxford Collocations Dictionary

+ Word Origin

Let's take a closer look at the entry for acknowledge from the beginning. Online, users can click ![]() to view other items from the Oxford 3000 wordlist which are at B2 CEFR level in alphabetical order. When using the

to view other items from the Oxford 3000 wordlist which are at B2 CEFR level in alphabetical order. When using the ![]() function, a pull-down menu with Oxford 3000, Oxford 5000, and Oxford 5000 excluding Oxford 3000 appears, and words from levels A1 to C1 (multiple levels can be selected) can be displayed. Users can also

function, a pull-down menu with Oxford 3000, Oxford 5000, and Oxford 5000 excluding Oxford 3000 appears, and words from levels A1 to C1 (multiple levels can be selected) can be displayed. Users can also ![]() the following PDF lists:

the following PDF lists:

The Oxford 3000

The Oxford 3000 by CEFR level

The Oxford 5000

The Oxford 5000 by CEFR level

American Oxford 3000

American Oxford 3000 by CEFR level

American Oxford 5000

American Oxford 5000 by CEFR level

Clicking on a word on the screen list will open that word's entry. Users can hear the English or American pronunciation of that word by clicking on the blue ![]() or red

or red ![]() speaker icon. They can also search the displayed list by typing a word in the search box.

speaker icon. They can also search the displayed list by typing a word in the search box.

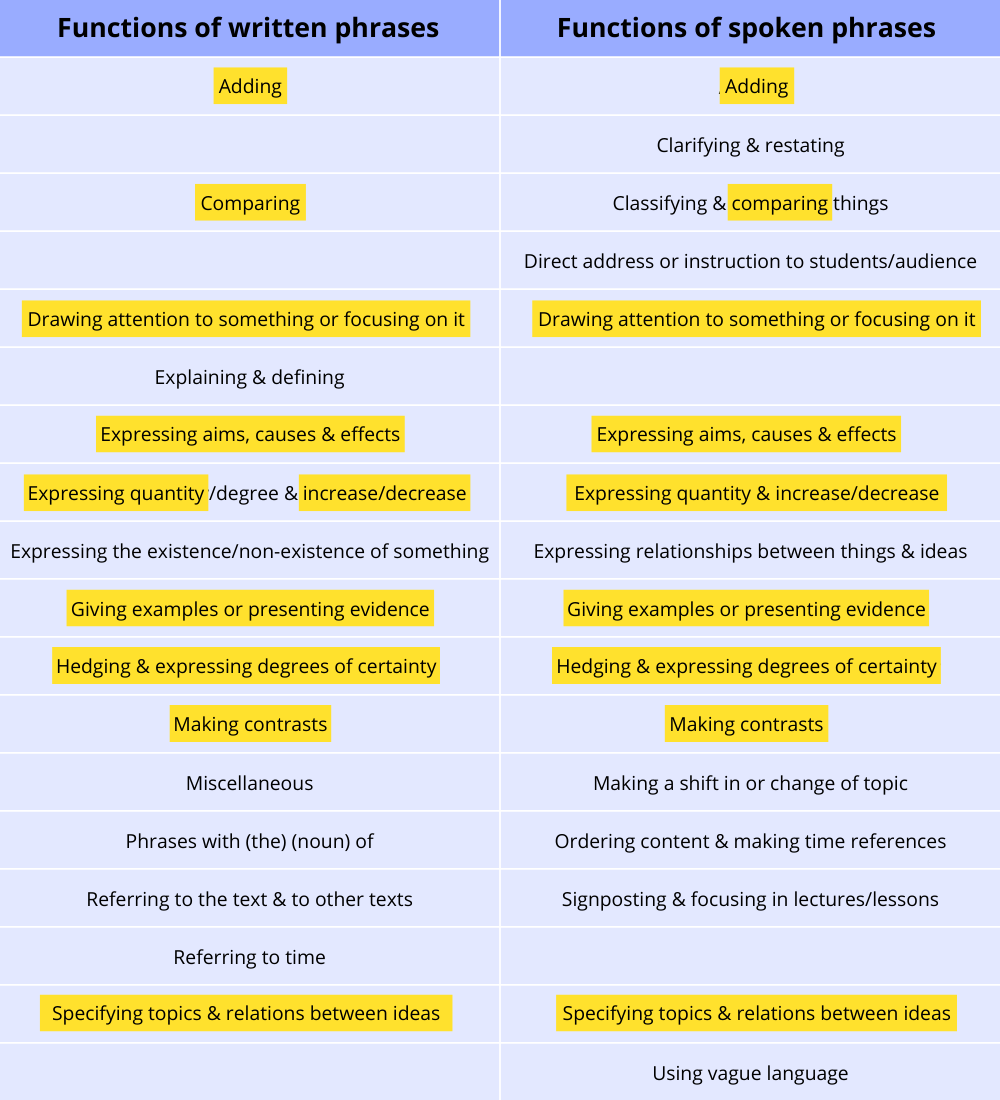

By clicking ![]() , users can view items from sublist 10 of the written words list in the Oxford Phrasal Academic Lexicon (OPAL). OPAL is a newly developed corpus-based list of important words in academic English from Oxford University Press. It consists of four lists: written words, spoken words, written phrases, and spoken phrases. The written words list has 1200 keywords in 12 sublists of 100 words each, and the spoken words list has 600 keywords in six sublists of 100 words each. Sublist 1 in each category contains the most important terms, followed by the most important terms in descending order. The list of phrases is organized by function. The written phrases list contains approximately 370 phrases in 15 functional sublists, and the spoken phrases list contains approximately 250 phrases in 16 functional sublists.

, users can view items from sublist 10 of the written words list in the Oxford Phrasal Academic Lexicon (OPAL). OPAL is a newly developed corpus-based list of important words in academic English from Oxford University Press. It consists of four lists: written words, spoken words, written phrases, and spoken phrases. The written words list has 1200 keywords in 12 sublists of 100 words each, and the spoken words list has 600 keywords in six sublists of 100 words each. Sublist 1 in each category contains the most important terms, followed by the most important terms in descending order. The list of phrases is organized by function. The written phrases list contains approximately 370 phrases in 15 functional sublists, and the spoken phrases list contains approximately 250 phrases in 16 functional sublists.

*Features common to written and spoken phrases are highlighted.

Clicking![]() will reveal the following pull-down menu, allowing users to filter by list (words by importance, and phrases by function) to display relevant words and phrases:

will reveal the following pull-down menu, allowing users to filter by list (words by importance, and phrases by function) to display relevant words and phrases:

Dictionary: Academic English/English

Word List: OPAL written phrases/ OPAL spoken words/OPAL written words/OPAL spoken phrases

The following PDF lists of key words in Academic English organized by sublists can be downloaded:

OPAL: written single words

OPAL: spoken single words

OPAL: written phrases

OPAL: spoken phrases

Let’s return to the main page for acknowledge. By clicking the blue and red speaker icons in front of the phonetic symbols, users can hear the English and American pronunciations. Also, as you can see from the pictures below, the print version uses symbols and abbreviations in bold type to show the example structures (~ represents acknowledge, sth is short for ‘something’, and sb for ‘somebody’), whereas they are fully written out in the digital version. In addition, sense 1 of the online version contains three examples not included in the print publication.

By looking at the entries for acknowledge, we can see that the online version is easy to read and contains a large amount of information. Additional information is organized into different sections in order not to sacrifice readability. In the print age, when space was precious, every effort was made to make maximum use of a limited space.

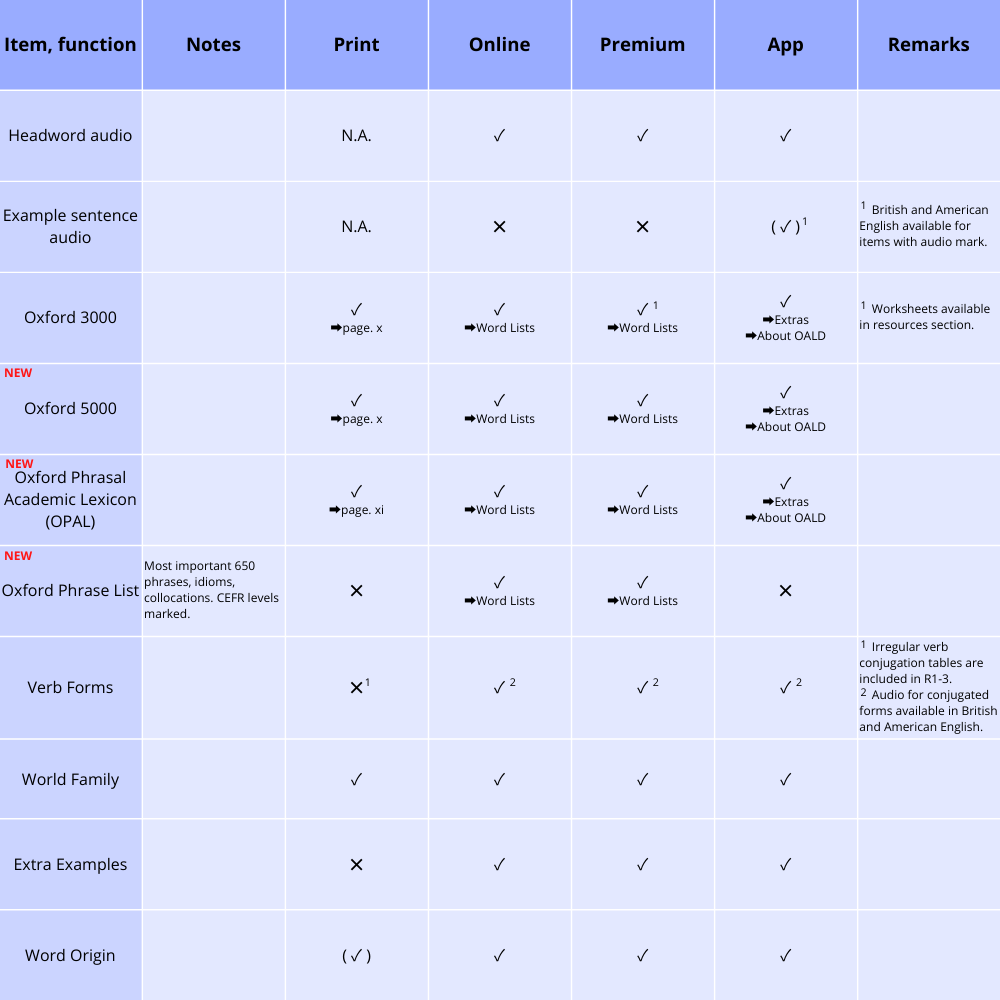

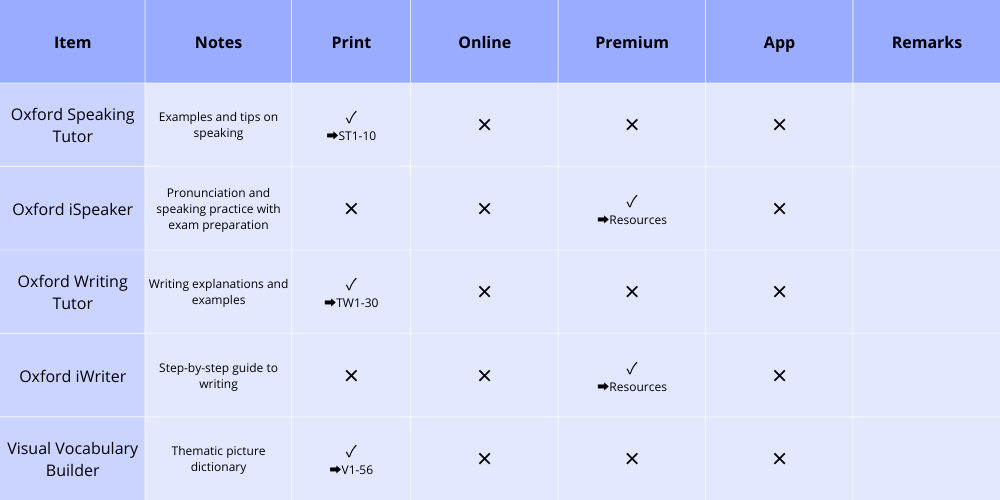

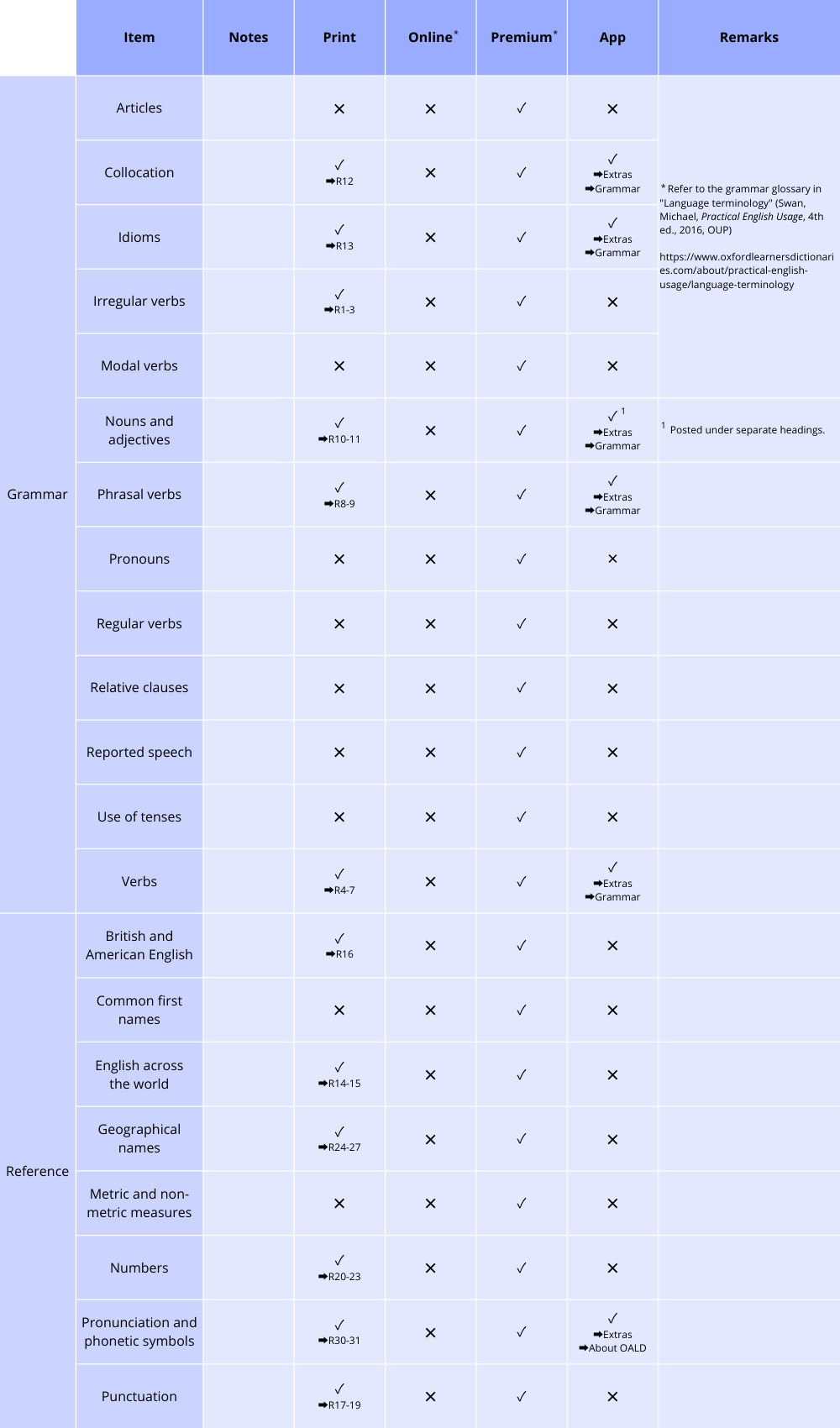

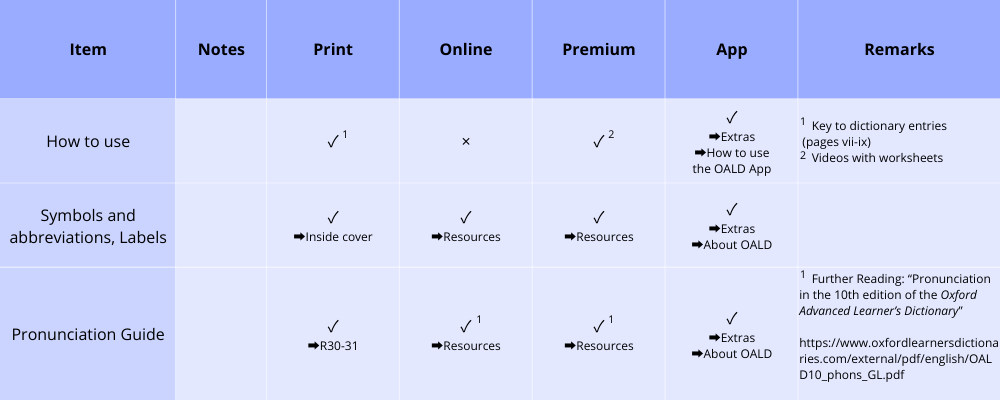

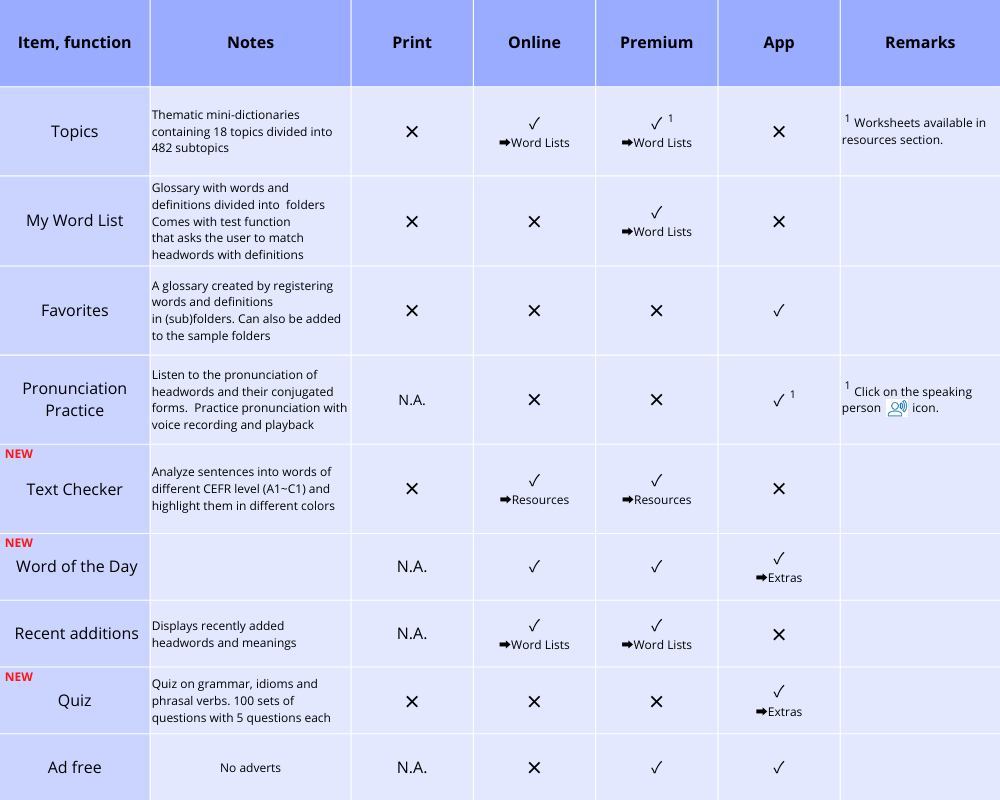

The OALD is currently available in print, online (for free), premium online, and the app (Google Play / App Store). The access code for the app and the premium online can be purchased with the print dictionary, and also the premium online access code can be purchased separately. OALD now goes beyond the traditional framework of a "dictionary" and provides guidelines for vocabulary learning, as well as comprehensive support resources for learning and teaching English. It also provides information, functions, tools, and materials that are useful not only for searching, but also for learning and teaching. I have listed the most important of these tools and where to find them under the following headings:

General information

Columns

Search

Appendices

How to use the dictionary

Others

I hope that the information in this article will help you to get the most out of the wonderful resources available with the OALD.

Reference:

Takahashi, Rumi, et al. 2021. “An Analysis of Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English, Tenth Edition.” Lexicon. No. 51. Iwasaki Linguistic Circle. 1-106.

Usage guide:✓ = available, (✓) = partially available, X = unavailable, N.A. = not applicable. Locations are indicated below the symbols where appropriate.

NEW = introduced with OALD10 (2020).

●General information

●Columns

●Search

●Appendices

〇References (reference pages on the OALD Premium online)

●How to use the dictionary

●Others

Author Profile

YAMADA Shigeru

Professor at Waseda University, Tokyo. He is on the editorial advisory board of Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America. He was a Co-Editor-in-Chief of Lexicography: Journal of ASIALEX. His specialization is EFL and bilingual lexicography. His publications include: “Monolingual Learners’ Dictionaries – Past and Future” (The Bloomsbury Handbook of Lexicography, 2nd ed., Ch. 11, 2022)

Guide to the practical usage of English monolingual learners’ dictionaries: Effective ways of teaching dictionary use in the English class (2014, Oxford University Press)

https://www.oupjapan.co.jp/sites/default/files/contents/catalogue/oald/media/oup_guide_to_dictionary_use_2014_e.pdf

Using English-English Dictionaries in the Secondary Classroom Vol. 2

Read the first article.

One strategy I recommend to all teachers who want to make sure their students keep doing an activity inside and outside of the classroom: prioritize that activity and do it in every lesson without fail. For example, if your goal is for students to learn to read aloud, you must ensure students practice reading aloud in every lesson, or they will not do it at home. I believe this is also true for shadowing, listening, or any other exercise.

Teachers usually set homework assignments using physical items such as worksheets and notebooks, so it’s easy to check students’ work. But for tasks such as reading aloud, shadowing, listening, and looking words up in dictionaries, it’s more difficult to confirm whether or not students are actually doing them. In the past, I used a check sheet for reading aloud and had students submit it every week, but there was no way to know whether they were being honest. In other words, we have no choice but to believe our students. Often students would hand in meticulously written check sheets, but when I listened to them reading passages aloud, I was doubtful they had really practiced.

When I was younger, I often worried about whether my students would form genuine study habits if I entrusted them to work independently. I decided to carefully observe what my students worked diligently on in class and which homework activities they were enthusiastic about. This led me to an important discovery. Students work harder on things that they know they will be evaluated on. It's an obvious point, but one that I had completely overlooked. I then redesigned my classes to have a stronger emphasis on the exercises that I wanted students to practice every day. Once students had become confident with reading aloud, shadowing, and extensive reading in class, I could trust them to do those activities at home as too.

The same principle applies to using monolingual dictionaries in the classroom. That is, always refer to an English-English dictionary in every lesson, at any opportunity, and without exception.

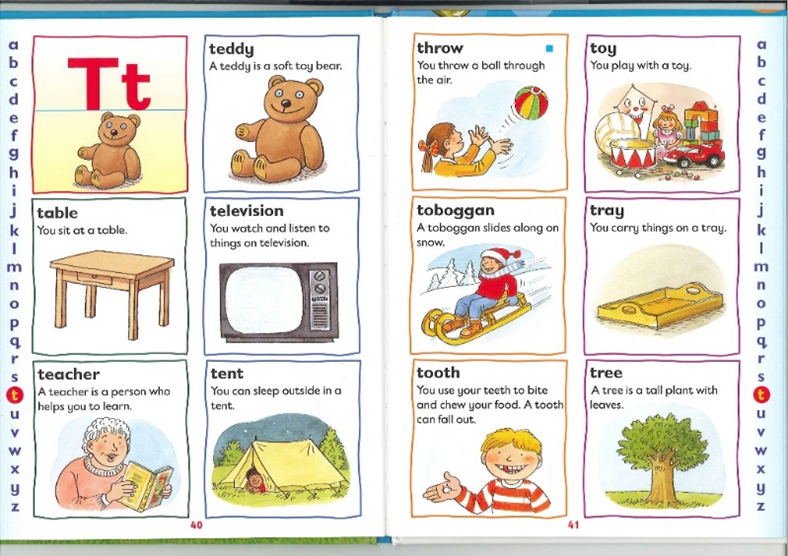

I have been using English-English dictionaries in my lessons for 6 years, and I make sure that there is some time for dictionary work in every class. All my students have a copy of the Oxford Basic American Dictionary (Oxford University Press. Out of print and while stocks last), and we use it to look up words that appear in textbooks, vocabulary lists, reading and listening passages.

Every time students use a dictionary, they should also check the grammatical terms. If not, they forfeit half the benefit of using a dictionary. This practice helps them realize that the English grammar they learn in the classroom has its life outside in the real world.

Tip:Have students refer to their dictionaries and take notes during activities such as reading aloud, using textbooks, group discussions and active learning

When reading aloud or explaining the contents of textbooks, it’s best not to explain the meaning of words in Japanese or have students look them up an English-Japanese dictionary straight away. Instead, make students use an English-English dictionary and practice taking notes. We should put aside any fear that students may not understand definitions in English. In second language acquisition, worrying too much about learners can hinder acquisition.

When I ask my students to look up words in an English-English dictionary, they react completely differently to how I would expect. They go ahead and look up the word without any complaints at all. When I tell them to look at the English sentences and think about the meaning with their friends, they will start guessing the meaning in pairs or groups. After that, I provide simple explanations such as, “If you take the first part of this sentence it will make this …”, and then give further instructions. Doing this is very important.

Just looking up one word isn’t enough for effective learning. It is important to repeat the same activity for the sake of continuity and to develop long-term learning habits.

I often ask my students what they think the other parts of speech for a word will be and then to check, then look up another word. They quickly get the point and feel satisfied.

I repeat this activity by changing the parts of speech that students look up in the dictionary in each lesson, such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and articles. After repeating this for about two weeks, they will become accustomed to looking up words in English-English dictionaries without difficulty. Let’s look at an example. If you look up the verb “go”, you will find the definition, “to move or travel from one place to another.” I explain each part of the definition in Japanese from the beginning. Next, I ask students to look up the verb, “come”. They will find the definition, “to move to or towards a person or place.” Again, I explain each part of the definition in Japanese.

Students can recognize two points about English grammar here: the verb is explained with “to do", and the preposition shows the direction. Even if I don't make full use of grammatical terms in detail, I can touch on many grammatical items just by explaining the meaning of words in an English-English dictionary. You can naturally understand how sentences are generated and how grammatical meanings are formed. I then repeat this for the other parts of speech.

I taught the meaning of the infinitive “to do” to my first-year junior high school students before covering it in grammar class. To illustrate, the Oxford Reading Tree Dictionarydefines the word “address”as, “Your address is the place where you live.” I used this definition with my first-year students without touching on the grammar, and it worked very well. Beginner-level English learners in their first year of junior high school cannot yet understand detailed grammar such as noun clauses, so at this stage, it’s enough for them just to read and comprehend the overall meaning. Later, when the teacher explains the grammar, students will realize how the English language is structured. It’s important to take students through the steps: familiarity, habituation, use, and grammar comprehension. This process simulates how young children learn languages.

Introducing some of these changes may feel troublesome at first, but by being consistent and using these techniques in every class, students will quickly get used to them and develop positive learning habits. When I was a high school student, we always used an English-Japanese dictionary for classroom activities and homework and this just became a natural part of studying. The same is also true when the teacher asks their students to use an English-English dictionary in every lesson.

As we have seen, there are many benefits to using English-English dictionaries. I hope that the ideas in this article help you move away from translation toward all-English study; providing students with the skills they need for effective language learning.

Special interview with characters from Oxford Reading Tree: Learning at home with Oxford Reading Tree

~For anyone currently using or thinking about using Oxford Reading Tree~

今回は森藤ゆかりさん(ビコさん)をゲストにお招きしてOxford Reading Tree (以下ORT)を使用した子育て方法について対談形式でお伺いいたしました。

① これからORTを使おうとしている方に向けて

A: 息子が4歳の時、初めて本屋さんで「買って」と持ってきた絵本がORTでした。タイトルは”The Toys' Party”です。

我が家では息子が1歳前から少しずつ英語のCDを聞かせていたのですが、いずれは読書できるようにしてあげたい、と思っていたので、ORTを見て「これは、息子にちょうどいい」と感じました。薄手の絵本パックで量があり、内容も理解しやすく、何より子ども(キッパー)が生き生きと描かれていることに温かみが感じられて、とても気に入りました。

A: ………続く

対談記事全文ではORTのキャラクターたちが登場しビコさんにお話をお伺いしています。こちら よりお読みいただけます。

森藤 ゆかり(ビコさん)

自身の子育てを機に、英語子育てサイトR-Train開設。以後20年以上、コミュニティやメディアで英語や家庭教育について情報発信を続けている。

息子は、バイリンガルに育ち東京大学へ。

著書「+(プラス)えいごではなまる子育て」、絵本の活用法など多数。

Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary: Now and then

In 2020, the 10th edition of the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, or OALD, was published. The origin of this dictionary can be traced back to the Idiomatic and Syntactic English Dictionary (ISED), the world's first fully-fledged English-English dictionary for English language learners. ISED was edited by A. S. Hornby and others, who were invited from the United Kingdom to engage in English education in Japan, and was published by Kaitakusha in 1942. 2022 marked the 80th anniversary of the ISED. During that time, as English was established as the international language of communication, the rivalry between different publishers has, together with the development of (applied) linguistics and lexicography, contributed to the ongoing evolution of monolingual dictionaries for language learners.

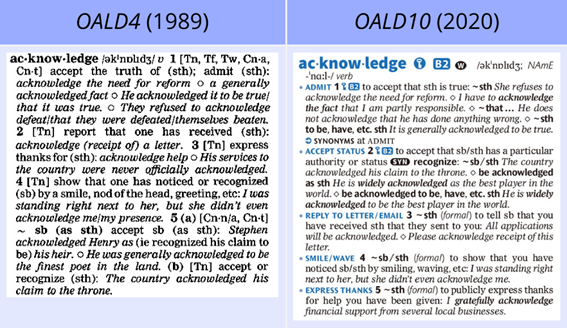

Since the mid-1990s, the quality of information has improved, and monolingual dictionaries have become easier to use. The key concepts are “corpus basis” and “user-friendliness”. To appreciate what kinds of changes have occurred, let's compare the entries of acknowledge in the 4th edition (1989) and the 10th edition (2020) of OALD.

Firstly, compared to the 4th edition, the 10th edition is easier to read; it is printed in two colors with each definition written on a new line. The OALD has been printed in two colors since the 6th edition (2000). Furthermore, in the 10th edition, notice these symbols next to the headword:  ,

,  , and

, and  . What do these symbols represent?

. What do these symbols represent?

The Oxford 3000TM and The Oxford 5000TM

The key symbol (  ) indicates that the word is from the Oxford 3000 wordlist. This is a list of 3000 words that students of English should learn first, and was introduced in the 7th edition (2005) and revised for the 10th edition. The words have been selected based on frequency and relevance for the user. Frequency of use is determined by the Oxford English Corpus (which contains more than 2 billion words), and relevance by a specially created corpus of secondary and adult English courses published by Oxford University Press. Also, every definition in the OALD is written using words from the Oxford 3000, making the definitions easier to understand.

) indicates that the word is from the Oxford 3000 wordlist. This is a list of 3000 words that students of English should learn first, and was introduced in the 7th edition (2005) and revised for the 10th edition. The words have been selected based on frequency and relevance for the user. Frequency of use is determined by the Oxford English Corpus (which contains more than 2 billion words), and relevance by a specially created corpus of secondary and adult English courses published by Oxford University Press. Also, every definition in the OALD is written using words from the Oxford 3000, making the definitions easier to understand.

The key symbol with a plus sign (  ) refers to words from the Oxford 5000, which was introduced in the 10th edition. This introduces an extra 2000 words for higher-level students to learn. The key symbols for the Oxford 3000 and 5000 are not just added to the headwords but also to the definitions.

) refers to words from the Oxford 5000, which was introduced in the 10th edition. This introduces an extra 2000 words for higher-level students to learn. The key symbols for the Oxford 3000 and 5000 are not just added to the headwords but also to the definitions.

*Find out more about the Oxford 3000TM and the Oxford 5000TM wordlists.

https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/wordlists/oxford3000-5000

Common European Frame of Reference (CEFR)

The Common European Frame of Reference divides foreign language competencies into six levels – A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, and C2. Words from the Oxford 3000 are labeled  -

-  , and words from the Oxford 5000 are

, and words from the Oxford 5000 are  or

or  .

.

The Oxford Phrasal Academic LexiconTM (OPAL)

is an abbreviation for written, indicating that acknowledge is an important word in written academic English. Academic English is crucial for most users of the OALD, particularly those studying abroad or taking classes in English. Oxford University Press created The Oxford Phrasal Academic Lexicon (OPAL) from an analysis of two corpuses: Oxford Corpus of Academic English (which contains 71 million words) and British Academic Spoken English (which contains 1.2 million words). OPAL includes important words and phrases from both written and spoken academic English. In OALD10, words and phrases from the written academic English section of OPAL are signified by

is an abbreviation for written, indicating that acknowledge is an important word in written academic English. Academic English is crucial for most users of the OALD, particularly those studying abroad or taking classes in English. Oxford University Press created The Oxford Phrasal Academic Lexicon (OPAL) from an analysis of two corpuses: Oxford Corpus of Academic English (which contains 71 million words) and British Academic Spoken English (which contains 1.2 million words). OPAL includes important words and phrases from both written and spoken academic English. In OALD10, words and phrases from the written academic English section of OPAL are signified by  , and words and phrases from the spoken academic English section by

, and words and phrases from the spoken academic English section by  . Words that are used in both written and spoken English are marked

. Words that are used in both written and spoken English are marked  .

.

*Find out more about OPAL.

https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/wordlists/opal

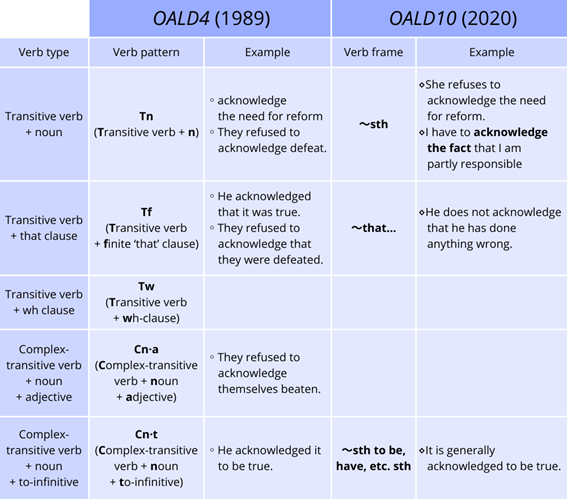

Grammar notation

Turning our attention to the 4th edition, we can see the first meaning of acknowledge contains these codes [Tn, Tf, Tw, Ca·n, Cn·t]. They indicate verb patterns. For example, [Tn] means transitive verb. Considering that this pattern was denoted by [VP6A] in the 3rd edition (1974), this is much easier to understand. Although a list of verb types could be found on the inside back cover of the 4th edition, referring to this each time was a real hassle. Though it takes up space, the grammar code is spelled out in the 10th edition (sb stands for somebody, and sth stands for something). In OALD10, these abbreviations, called “verb frames”, are written just before the corresponding example. The verb patterns and example sentences in OALD4 and OALD10 are summarized in the comparison table below. The clarity of the 10th edition is self-explanatory.

Shortcuts

Returning to OALD10, you’ll notice that each definition is preceded by a word or short phrase capitalized in blue and marked by a dot such as  . These are called “shortcuts”, and they show the context or general meaning of each definition at a glance. When using a monolingual dictionary, selecting the appropriate meaning can be a daunting task. Therefore, from the 6th edition (2000) on, "shortcuts" or "subheadings of meaning" were introduced to help users navigate polysemous entries. Instead of scrutinizing definitions and examples one by one, users can quickly scan the shortcuts, select the relevant one, and then examine the meaning.

. These are called “shortcuts”, and they show the context or general meaning of each definition at a glance. When using a monolingual dictionary, selecting the appropriate meaning can be a daunting task. Therefore, from the 6th edition (2000) on, "shortcuts" or "subheadings of meaning" were introduced to help users navigate polysemous entries. Instead of scrutinizing definitions and examples one by one, users can quickly scan the shortcuts, select the relevant one, and then examine the meaning.

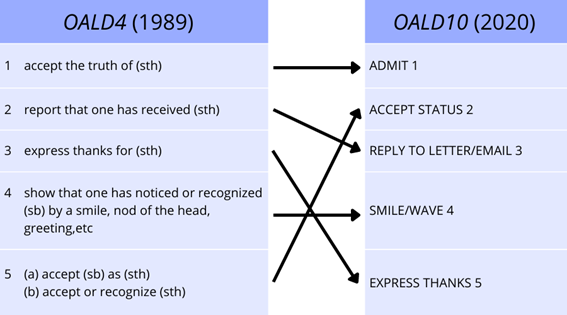

The influence of corpuses

Since the introduction of the Collins COBUILD English Language Dictionary in 1987, the use of corpuses has become an integral part of dictionary editing. Corpuses provide vital data on the frequency of usage for each word, and this influences every stage of lexicographic editing from identification and selection of headwords, through sense division and arrangement, identification of grammatical and lexical patterns, to the presentation of examples. Let's look at how the entries of acknowledge are structured in OALD4 and OALD10. There are differences between the two, and the latter is based on frequency from corpus analysis.

As you can see from the comparison table above, the verb types Tw and Cn·t shown in OALD4 are not included in OALD10. Based on corpus analysis, the frequency may not have been high enough. Frequent patterns such as acknowledge the fact are highlighted in bold in the examples.

The most recent editions of English-English dictionaries contain accurate information, presented in a format which is easy to understand and use. OALD10 has been edited based on large corpuses and displays the most high-frequency words. Innovations, such as the integration of the Oxford 3000 and 5000 wordlists and OPAL, make it easier for users to identify core vocabulary, the Oxford 3000 also making definitions easier to understand. In addition, shortcuts and straightforward abbreviations of verb patterns make the latest edition even more user-friendly. Whilst in the past dictionaries were only available in print, now it’s easy to find online versions. In my next article, I will explore the effects of digitalization on dictionaries, particularly on the editorial processes and how people search for words.

Reference:

Yamada, Shigeru. 2020. OALD10 Katsuyo Gaido [Usage Guide]. Tokyo: Obunsha Publishing.

https://dic.obunsha.co.jp/oald10/dl_guide_book/OALD10_dic.pdf

Author Profile

YAMADA Shigeru

Professor at Waseda University, Tokyo. He is on the editorial advisory board of Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America. He was a Co-Editor-in-Chief of Lexicography: Journal of ASIALEX. His specialization is EFL and bilingual lexicography. His recent publications include “Monolingual Learners’ Dictionaries – Past and Future” (The Bloomsbury Handbook of Lexicography, 2nd ed., Ch. 11, 2022).

Using English-English Dictionaries in the Secondary Classroom Vol.1

The ability to understand English without translating into Japanese is something that many Japanese learners of English dream of achieving. I know this because I often hear students remark, “I wish I could understand English movies without subtitles.”

When I was teaching English at high school, there was a moment when I switched from giving instructions in Japanese to only speaking English during classes, often referred to as “all English” learning. At first, the students and I felt unsure about this new approach, but we pressed on and hoped for the best, trying different approaches together and developing our lessons.

During speaking activities, I was concerned whether students who struggled with simple things such as explaining something or describing a scene in English would be able to express their opinions freely or react to other people’s opinions.

Once, while preparing for a lesson, I happened to glance at the bookshelf and caught sight of some old books I rarely used. Among them was my copy of the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. Flicking through it, I felt nostalgic upon finding words that I had underlined sometime ago. I decided to look up sushi, and found this definition: “sushi / noun / a Japanese dish of small cakes of cold cooked rice, flavored with vinegar and served with raw fish, etc. on top.”

Reading the definition reminded me of how you can use English to describe words such as sushi. It also brought to mind a segment from the television show Sesame Street in which adults explained new words to children.

I was worried about how my students would react if I introduced a new section to our class for using English-English dictionaries. As a student, I only studied with an English-Japanese dictionary: my teacher never recommended using an English-English dictionary, and I believed that only very high-level students would be able to understand definitions in English.

However, I soon realized there was no reason to worry, From the next lesson, I started getting students to use English-English dictionaries to make notes of definitions and explain words to each other in English during class. The students were not worried about the lack of Japanese translation, and they enjoyed reading the definitions in pairs and groups while working out the meaning of words together.

After about two years, I began to notice a change in my students’ written work. I used to have to spend a lot of time correcting and explaining the differences between Japanese and English syntax, but now there were far fewer mistakes. Also, when correcting their own work, more and more students would show me example sentences from their dictionaries and ask whether they should write sections of their compositions in a similar way. I remember how amazed and delighted I was by that change.

I used English-English dictionaries with my high school students for three years and felt strongly that this approach had many benefits. The next year, I was in charge of my junior high school’s first-year class and I recommended trying an all-English approach to my teaching partner. We invested in some picture dictionaries for the students, and used reading, listening and recitation activities, which encouraged students to understand English without translating. Three years have passed, and these students are now in the first year of high school. Each student has a mini English-English dictionary which they use during and outside of class, and it’s clear to me that the dictionaries have been very effective.

One of the benefits of using English-English dictionaries is that it encourages students to understand English without translating into Japanese. Of course, when learning new vocabulary it’s useful to know the Japanese translation, but understanding the meaning of English words in English helps learners to more naturally grasp grammatical rules as well.

In my next article, I will share some more of my experiences using English-English dictionaries.

Global skills for the primary EFL classroom in Japan

I began teaching English in Japan in October 2000. It’s strange to think that the elementary school children who I taught at the time are now adults, navigating life in the 2020s with all the challenges and opportunities of a global, technological society. Back in the early 2000s, I had no idea how life would change in the next 20 years and what skills or knowledge would be important for the future. I didn’t even own a mobile phone!

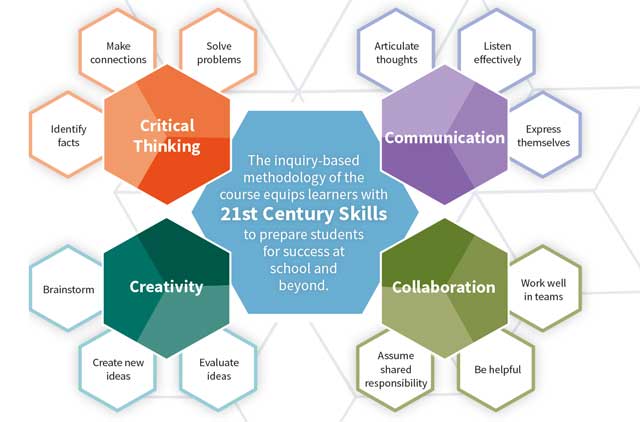

As the 21st century progresses, children increasingly need to receive an education which prepares them to deal with change and equips them with the skills needed for success in a fast-changing world. In our position paper on Global Skills, we identified 5 distinct clusters of skills essential for today’s learner: communication and collaboration; creativity and critical thinking; emotional self-regulation and wellbeing; digital literacies; and intercultural competence and citizenship. These skills are vital for students of all ages in their general education, and English classes provide a wonderful opportunity for children to develop these competencies from an early age. In this article, I will consider how 2 of the clusters (communication and collaboration and emotional regulation and wellbeing) can be applied to EFL classes for primary students in Japan.

Communication and collaboration

Students in primary EFL classes in language schools in Japan tend to study in relatively small groups. Typically, the majority of communication in English takes place between the teacher and students, with the teacher asking questions and the students answering. For example, when studying the question-and-answer pattern, “What’s your favorite (sport)?”, “I like (tennis).”, it is common for the teacher to ask the question to each student individually and the students to give their own answers. There is nothing wrong with this approach, but to foster genuine communication and collaboration skills, we need to encourage students to speak English to each other, perhaps in pairs or groups, and work together to achieve common goals. Depending on the task, we could even have students decide which roles they each take in order to complete it.

Students in primary EFL classes in language schools in Japan tend to study in relatively small groups. Typically, the majority of communication in English takes place between the teacher and students, with the teacher asking questions and the students answering. For example, when studying the question-and-answer pattern, “What’s your favorite (sport)?”, “I like (tennis).”, it is common for the teacher to ask the question to each student individually and the students to give their own answers. There is nothing wrong with this approach, but to foster genuine communication and collaboration skills, we need to encourage students to speak English to each other, perhaps in pairs or groups, and work together to achieve common goals. Depending on the task, we could even have students decide which roles they each take in order to complete it.

Here are some ideas for increasing communication and collaboration in the classroom.

・Teach students both the question and answer forms, and have them practice asking and answering questions in pairs. Although children can be reluctant to speak English to each other at first, with enough practice they will become more comfortable communicating with their classmates in English. Younger children in particular will need an activity to structure their conversation. For example, you could give each pair a set of small cards, have them turn their cards face down and mix them around. Students then challenge each other by pointing at a card and asking, “What’s this?”

・Set your students a project. Projects are a great way to get students working together. For example, put students into groups and ask each group to make a poster about healthy food. To complete the task, the children must first decide together which kinds of food to include (to make it easier, you could limit the number of choices and give a specific target such as 5 kinds of food). Members will need to discuss and agree on who in the group does what: Who will draw pictures of the food? Who will write the names of the food under each picture? Who will write the title? Who will add glitter or other decorations? Finally, each group gives a short presentation about their poster, again deciding who will talk about each food. Throughout the process, there may be children who want to do everything themselves and others who are reluctant to get involved in the activity, but by carefully structuring the task, setting clear goals, and monitoring the activity, the teacher can ensure that the children are learning how to work together to accomplish a task and contribute equally. Students naturally need to communicate with each other to make decisions, and classroom phrases are very useful to ensure that plenty of English gets spoken. In this case, we might want to teach, “Let’s draw (broccoli)”, “I’ll (write the title)”, etc.

・Set your students a project. Projects are a great way to get students working together. For example, put students into groups and ask each group to make a poster about healthy food. To complete the task, the children must first decide together which kinds of food to include (to make it easier, you could limit the number of choices and give a specific target such as 5 kinds of food). Members will need to discuss and agree on who in the group does what: Who will draw pictures of the food? Who will write the names of the food under each picture? Who will write the title? Who will add glitter or other decorations? Finally, each group gives a short presentation about their poster, again deciding who will talk about each food. Throughout the process, there may be children who want to do everything themselves and others who are reluctant to get involved in the activity, but by carefully structuring the task, setting clear goals, and monitoring the activity, the teacher can ensure that the children are learning how to work together to accomplish a task and contribute equally. Students naturally need to communicate with each other to make decisions, and classroom phrases are very useful to ensure that plenty of English gets spoken. In this case, we might want to teach, “Let’s draw (broccoli)”, “I’ll (write the title)”, etc.

Emotional regulation and wellbeing

Children will naturally go through an emotional journey in each class and throughout the overall learning process. It is important that they are aware of these emotions and can recognize similar emotional reactions in others, as these feelings serve as a compass in life telling us what is right and wrong for ourselves and others. Repressing strong emotions has been linked to depression in teenagers, and it is important to avoid this by teaching students healthy coping strategies as children.

Here are some helpful things to try in English classes.

・Use picture books. Stories help students to recognize the emotional reactions of characters and develop empathy. When doing group reading sessions, it’s always useful to draw attention to the characters’ feelings. For example, if there is a scene in which a character has dropped an ice cream, the teacher could ask, “How does the girl feel?”, “Why?”, “Do you like ice cream?”, etc.

・Use picture books. Stories help students to recognize the emotional reactions of characters and develop empathy. When doing group reading sessions, it’s always useful to draw attention to the characters’ feelings. For example, if there is a scene in which a character has dropped an ice cream, the teacher could ask, “How does the girl feel?”, “Why?”, “Do you like ice cream?”, etc.

・Ask children how they are feeling. By checking in with our students at particular moments of the class, teachers can encourage children to reflect on their emotional state. Avoid letting students reply with, “I’m fine, thank you” every time and encourage them to give genuine answers. They may be a little tired at the beginning of the class, then happy and energetic in the middle, hungry by the end. Noticing the children’s emotional state also helps teachers to adapt activities in class to keep them engaged.

The ideas above cover just 2 of the 5 Global Skills introduced in our position paper. Please join me at the Oxford Workshops for Primary Teachers this summer where I will share more practical ideas for teaching all 5 skills.

More about (not just) Phonics! Vol. 2

Kate Sato, associate professor at Hokkaido University of Science and experienced teacher trainer, kindly joined the Oxford Teaching Workshop Online in March 2021 to introduce some useful phonics activities for young learners.

In the final article of a two-part series, Kate provides even more advice for phonics instruction with different age groups, as well as some general tips on a variety of topics including classroom management and continued professional development.

Other factors

In the flow of my fifty-minute class we would spend 10-15 minutes on phonics each week until they had covered the course I had in my school, which would take about 2 years to cover. Following on from that we would continue to look at tricky spelling word groups. Teaching the 44 phonemes was the starting point, constantly synthesising the sounds into words, or pointing out word patterns in graded readers (having a few graded readers series in your school is one of the best investments you can make). If you are in a challenging teaching situation, such as a public elementary school with a big class, let me suggest a different Covid-19 friendly activity you can do as a ‘warm up’ each class.

I call it North-South-East-West. Choose four phoneme cards to teach that day. You’ll need some way to adhere the cards onto the walls. With the children seated and focused on you, start to put the cards on each of the four walls of the room (so one card on each wall). As you are doing this introduce the sound associated with the letter. When all the cards are on the walls ask the children to stand. Then they need to point to the letter of the sound you say. So, for example you say /b/. The children need to turn and point to the card with the letter ‘b’ on it. You can start slowly and gradually get faster. Also, when you do this as a review you can have students be the teacher. For this activity I suggest big cards. If you can print them yourself and the students progress you can start cards with two letters to blend the sounds together e.g. st, sl, sp, sn, etc.

As you know, young learners are not fluent in their own language. Nor, obviously, are they fluent in English. Therefore, it is good to remember they probably do not know many words they are hearing, and are seeing. Many words they are not familiar with. At about age 6 they become cognisant and vocal about ‘not understanding’. This is normal. However, in setting up your students for success I would try to avoid overwhelming them with too many new words at once.

Remember after you have introduced a sound, the children need time to process the information so they can recall and produce the sounds confidently.

Therefore, giving the children time and space for processing is critical, and something I do not recommend rushing. This is where the activities such as ‘denacard' and ‘race track race’ play an important role. Don’t be afraid of splitting the class into groups to give children more practice.

Lastly, in a regular class I would follow a routine (as illustrated in the article in The School House referenced below). I only teach a ‘whole phonics focused class’ when I am conducting research.

Teacher development

When I started my school in 2002 information on the internet was limited. Books were my teachers and I read a lot of them. Today I read more research journals. Whatever you read, it is important to continue your own professional development.

If you are having trouble with two sounds, for example the /u/ sound (as in “ cup”) and the schwa, a little knowledge can help. For this kind of issue it may be useful to refer to the IPA. You’ll see the two sounds are very similar. Also, if you are having problems, probably your students will too. As I mention below, don’t focus on this too much so it becomes a stumbling block. The schwa is a tricky sound. It’s made with the mouth more closed, and the tongue more forward. /u/ as in cup, however, is made with the mouth more open, and the tongue further back. We have different accents, you can play audio, or show a video, but I would say you are not going to teach the schwa when teaching phonics so don’t worry too much about it.

Please remember that phonics is a springboard for reading. There is much you can do with reading, from our very young learners to older learners! Just as we did an activity together, you can too! Reading with picture books is a great way to introduce a rich variety of vocabulary in context. I thoroughly recommend having ‘time for a book’ in the very young learner’s class each lesson.

Fonts & Writing

Learning to write with ‘correct stroke order’ is just as important with the alphabet as any other written script.

You will notice that publishers such as OUP use the Sassoon fonts in their young learner materials that come out of the UK. The Sassoon fonts are the educational fonts in countries like the UK and Australia.

If you teach the letter shapes with the joining tails (as with the Sassoon family fonts) I found by grade 4 upwards some children would link the letters themselves, but please note the children were exposed to joined writing on the board in the classroom.

You’ll be surprised at what children can do if you give them the chance. When teaching 3-year olds phonics you may like to try methods based more on Glenn Doman’s techniques with showing the cards. That would be a very quick activity in each class. Teaching a little, quickly (keeping agile), consistently every time is key. Please remember they are not too young to learn the sounds at this age, and to start to link the sounds to the letters. An activity may not work the first time you try it. I recommend trying it a minimum of 3 times and tweaking it to find what works for you and your students.

What I don’t recommend

What you do not do can be just as important as what you do do. What I mean by this is, keeping in mind that whatever I do I want to set the students up for success, this means as a teacher it is best to have SMART (specific, measurable, realistic, timed) goals. You cannot teach everything once a week in a 50-minute class. Therefore, you need to stay focused and let some things into the classroom, but not become the focus of the class. One example is the "le" card in Floppy Phonics.

I never taught the double ‘ff’ makes the /f/ sound, but when prompted the student could reason and guess that ‘ff’ made the same sound as ‘f’. In the same way I may not overtly teach the ‘le’ letter combination. Rather I would throw it down in the mix and see if the students could use logical reasoning to work out that the corresponding sound is the same as that for the single letter and double letter ‘l’.

Ultimately, however, as a teacher you need to decide what is YOUR system. The “le’ letters produce the same sound as ‘l’ so there is no harm in exposing the young student to that letter combination after a while, as a ‘throw away’. Later, if you wish, you can bring your students to a point where you require production rather than just recall. If you look on the internet there are many systems like the ‘get reading right’ one listed in the sources below.

When running a school I did not make an issue out of something that did not exist. Therefore, if a student asked me about the difference between what they learned elsewhere and what they learned with me, I would point out that that is good for there, and what I teach is good for my classes. Confusion can arise between romaji and English. Simply point out that romaji is Japanese, and English is English and children can settle back into focusing on learning English.

Likewise, I did not make an issue between US and UK English. There are many Englishes around the world, not just UK and US English. The teacher taught the English they were comfortable with, and it is enough to point out, when necessary, what ‘another version’ might be. To make progress follow a syllabus (textbook) and stick with it. I would avoid complicating things unnecessarily. After all, you don’t want to confuse your learners. If they pick up on a difference, just affirm the difference, but you don’t have to make that into what can become a stumbling block. After all, you want to build confidence.

Finally, please remember you can go (back) to the workshop and review any points. There are lots of materials and resources on the market, and internet. It is best you look around and see what suits your pedagogical requirements. I’m sure a representative will be happy to help you find what you are looking for.

Sources

・Cowan, N., Morey, C. C., AuBuchon, A. M., Zwilling, C. E., & Gilchrist, A. L. (2010). Seven‐year‐olds allocate attention like adults unless working memory is overloaded. Developmental science, 13(1), 120-133.

・Doman, G., Doman, J., & Aisen, S. (1975). How to teach your baby to read. Gentle Revolution Press.

・Fry, E. (2004). Phonics: A large phoneme-grapheme frequency count revised. Journal of Literacy Research, 36(1), 85-98.

・http://www.getreadingright.com.au/synthetic-phonics-teaching-sequence-letters-and-sounds/

・Sato, K.J.M. (2018) Factors to Consider in Creating Optimum Learning Environments (OLE) for the Young Learner’s EFL Classroom. The School House, 26(1) 19-25

More about (not just) Phonics! Vol. 1

Kate Sato, associate professor at Hokkaido University of Science and experienced teacher trainer, kindly joined the Oxford Teaching Workshop online in March 2021 to introduce some useful phonics activities for young learners. In this series of two articles, Kate provides even more advice for phonics instruction with different age groups, as well as some general tips on a variety of topics including classroom management and continued professional development.